by Eylem Yanardagoglu*

It unfolded in front of my eyes on three screens, my TV, my tablet and my smart phone. I followed social media timelines and chat threads until early hours of the morning while I panicked over sonic booms of low-flying jets over my building. The next day, and many days that followed I was overwhelmed with keeping up with the rolling 24 hour news coverage.

The putsch did not cut the internet connection. It attempted to disrupt the wider telecommunications infrastructure. In Istanbul a group of soldiers attempted to take over the private CNNTurk TV station and halt broadcasting. But instead their attempt was broadcast live to millions of viewers. The internet editors distributed the live content on Facebook to hundreds thousands of followers. Their videos on Facebook alone are estimated to have reached 8.5 million people.

President Erdogan, who loathed Twitter as “menace”, and despised new platforms, resorted to online media broadcast remitted via CNNTurk screens. On that night he was adressing the nation on CNNturk editor's Iphone which she held against the camera with a microphone. Ironically, a licensee of CNN, CNNTurk belongs to Doğan Media Group which Mr. Erdoğan exerted drastic economic pressures via levying heavy tax fines since 2007 for being critical of AKP policies. The use of Facetime was labeled by CNNTurk as a “world-wide journalistic achievement” and a “call of democracy”. For some techno-enthusiast commentators use of internet and social media “reinforced democracy” and curbed the power of the rouge (delete this word) soldiers that night.

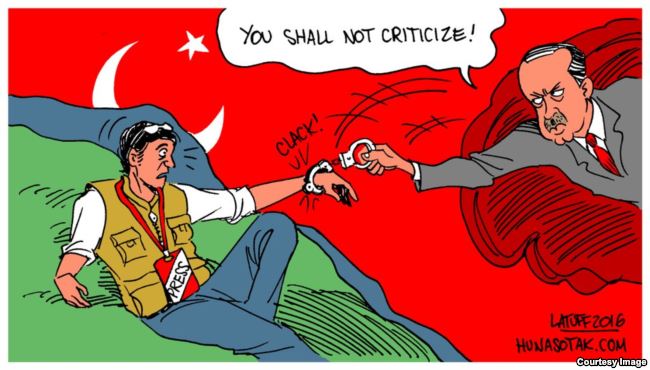

Turkish Union of Journalists estimated that by the end of June 2017 there were 159 journalists in prison, and approximately 200 media outlets are shut-down. It is hard to account for all the cases but the charges usually comprise of allegations such as being members of an armed organization, plotting against the government and terrorism propaganda. Eleven journalists of Cumhuriyet, the oldest newspaper in Turkey, have been in prison for more than 250 days. An emergency rule (OHAL)

was declared on the 20th of July last year for three months. It still stands to this date.

The first democratically elected government in Turkey was ousted by the first military intervention in 1960. Its leaders, indicted for abusing radio broadcasts for propaganda, among other accusations, were later executed. The TRT (Turkish Radio and Television Corporation) was founded in the post-coup context as an autonomous public broadcaster lost its autonomy in the second military intervention on 12th March 1971. It eventually turned into a mouthpiece of governments. The military coup of 12th September 1980 also held print and broadcasting media under tight control. The introduction of neoliberal economic policies after the coup paved the way for business elites, with investments in finance, banking and construction, take over media outlets in order to gain intellectual and political influence. The consolidation of ownership created a mutual dependency between the state and media. Journalistic values were jeopardised by clientalism as media owners became dependent on state loans and benefits. Turkey suffered some of the worst media freedom records in 1980s and 1990s.

In early 2000s, when President Erdoğan first came to power, he was a champion of free speech. Many reforms were introduced as part of EU harmonization process to make the media more free. In 2008, in AK Party's second term in power, the Constitutional Court levied its leaders a heavy fine for anti-secular activity. Although the court did not ban AKP; the AKP leaders believed that it was due to the the secular, Kemalist mainstream media that the party was getting “bad press”. Mr Erdoğan in a famous speech, openly challenged the editorial policies of such media organisations that does not support AKP policies and called on the public “not to read” such newspapers. A system know as the “pool media”, a pro-AK party partisan media owned by pro-AKP businessmen, were set during this period.

Until the end of 2013, the pro-Gülen movement, which is now known as the Fettullah Terror Organization (FETO) that masterminded the failed coup, supported media outlets such as Zaman, Bugün, Taraf which were considered to be part of the partisan media that supported the AKP policies. The movement's media, now banned, were believed to be instrumental in manipulating a particular agenda though journalists, through the use of leaked and often fabricated documents. The editors of the newspaper are Taraf newspaper, who are now in prison, famously pitched the headline ” not arrested for doing journalism” for journalists Ahmet Şık and Nedim Şener in 2011, who were investigating the Gülen movement. The coverage of Taraf in this period continue to stir massive debate among the media professionals about journalistic inregrity, responsibility and media freedom.

At the end of 2013 when voice recordings of politicians, including the President, were leaked on the internet, revealing corruption scandals, the authorities believed the Gülenists leaked the recordings in order to topple the government. In that period the online media such as Youtube and Twitter were blocked several times and the newspaper Zaman journalists and editors were arrested. Since2013 many journalists had lost their jobs.

In the three governments decrees that are introduced during the first six months that followed the failed coup, 5 news agencies, 23 radios, 62 newspapers, 19 magazines and 29 printing houses and distribution channels were shut down

Following the introduction of the emergency rule, Reporters Sans Frontier's published a report regarding the purge in the media. In the three governments decrees that are introduced during the first six months that followed the failed coup, 5 news agencies, 23 radios, 62 newspapers, 19 magazines and 29 printing houses and distribution channels were shut down on suspicion of “collaborating” with the Gülen movement.” One of the executive decrees of the emergencey rule ordered the closing down of 20 pro-Kurdish, leftist and oppositional TV and radio channels and banned access to their websites.

Last month, durign the holy month of Ramadan, journalist, and opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) deputy Enis Berberoğlu was arrested on June 14 after a court sentenced him to 25 years for reports published in the Cumhuriyet daily, suggesting that trucks operated by the National Intelligence Agency (MİT) transferred weapons to armed jihadists in Syria. The then chief editor of Cumhuriyet, Can Dündar, had also been charged for publishing these documents. Dündar left Turkey after being released from prison.

On the 17th of June, President Erdoğan invited around 180 journalists and representatives of media outlets for a fast-breaking (iftar) dinner and said that he receives comments about the high numbers of jailed journalists in Turkey when he travels abroad, but only 2 of these imprisoned journalists hold a valid yellow (official) press card, and they are mostly being held for having a relationship with terrorist organizations.

“Had the coup been successful: The TV stations and newspapers would be shut down, journalists would be put in jail and there would be one-sided journalism. The coup attempt failed. But lets see what happened afterwards”

Since last July many journalists have either been sentenced, imprisoned or fled the country. The struggle for media freedom continues, as Turkey still holds the world record for having the highest number of journalists in jail. A senior editor at the left-leaning newspaper Evrensel told me in a private interview:

“If you are an experienced journalist you would know what to expect, had the coup been successful: The TV stations and newspapers would be shut down, journalists would be put in jail and there would be one-sided journalism. The coup attempt failed. But lets see what happened afterwards: The oppositional media outlets are shut down, journalists arrested. Apart from a couple of newspapers and internet sites there are no outlets that can do different type of news. It is one sided publishing. It had not been easy to do journalism in Turkey. In the past and similar periods existed. But little crumbles of law could be enforced. Now this does not exist. I have received prison sentence, it is postponed. All we did was covering news about operations conducted in the Kurdish cities. I am a young journalist but I have never experienced a period when it was more difficult to write, to post things on social media. I now think twice before I write each word. Journalists were killed in the 1990s, but today journalism is being killed. But we will cry for this. If I do not insist on doing journalism, I would be hiding the truth. I believe we will come thorugh these dark days through solidarity between readers and journalists”.

A veteran journalist who is an editor for an online media platform also said: I predicted that Turkey would enter a new phase after the 15th of July. The continuity of the emergency rule since last year meant that all journalists, expect the oppositional ones, have internalized self censorship. In Turkey there has always been pressures on the media, but what has changed after the 15th for July is this: the political power is not doing it in a shy or careful way like they used to do. It is done openly. We are going through a period where an opaque “terrorism threat” is used to normalize pressures on the freedom of expression.”

Critics similarly believe that this current climate against journalists do not only target the media and media professionals, but gives a strong message that they can not do journalism any longer, unless they do it in the way authorities deem proper.

In Turkey the military coups always shaped the media scene and democratic institutions that emerged after the interventions. Last year's failed coup may have been televised, tweeted and facetimed, yet one year on, looking at its aftermath, I am left with a feeling that not much has changed since my childhood.

*Eylem Yanardagoglu is an Associate Professor at the New Media Department of Kadir Has University in Istanbul.