For the period from January to November in 2013 Greece’s state budget registered a primary surplus of 2.7 billion euros according to the country’s finance ministry. Earlier in december deputy finance minister Christos Staikouras said, ““After several years, the country will this year achieve a primary surplus earlier than expected, a surplus which in structural terms is the highest in Europe.”

Mr Staikouras added that this means that the general government budget’s primary surplus will exceed 800 million euros at the end of the year as calculated by the bailout agreement and that Greece’s creditors are in agreement with the finance ministry’s forecast. Indeed speaking in November at the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung΄s conference in Berlin, Angela Merkel praised Greece’s efforts, saying of the surplus, ““many in the troika did not believe that it could be achieved, but despite everything, it was achieved”.

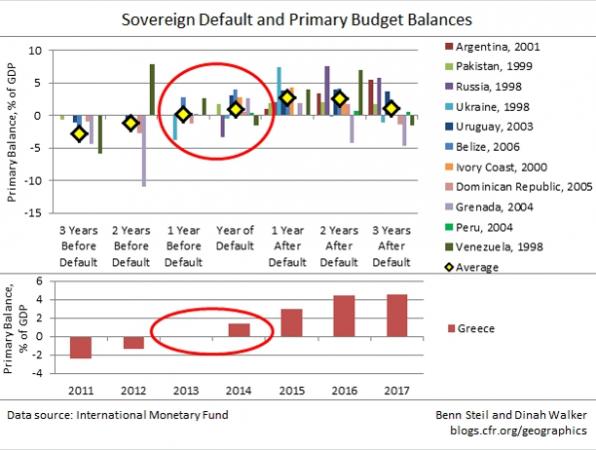

However some influential analysts are saying that the primary surplus is actually a cause for concern for Greece’s european lenders as it inevitably increases the country’s incentive to default. According to a recent article posted by the Council of Foreign Relations on it’s blog:

“A primary budget surplus is a surplus of revenue over expenditure which ignores interest payments due on outstanding debt. Its relevance is that the government can fund the country’s ongoing expenditure without needing to borrow more money; the need for borrowing arises only from the need to pay interest to holders of existing debt. But the Greek government (as we have pointed out in previous posts) has far less incentive to pay, and far more negotiating leverage with, its creditors once it no longer needs to borrow from them to keep the country running.

This makes it more likely, rather than less, that Greece will default sometime next year. As today’s Geo-Graphic shows, countries that have been in similar positions have done precisely this – defaulted just as their primary balance turned positive.

The upshot is that 2014 is shaping up to be a contentious one for Greece and its official-sector lenders, who are now Greece’s primary creditors. If so, yields on other stressed Eurozone country bonds (Portugal, Cyprus, Spain, and Italy) will bear the brunt of the collateral damage.”

So while Greek officials including prime minister Antonis Samaras are optimistically predicting a return to growth and normalcy for the country in 2014, for many the spectre of a Greek default remains very much a possibility with unpredictable consequences for the European economy.

Whether that actually happens remains to be seen but it certainly does appear that Greece is gaining a certain degree of leverage in negotiations with its lenders. What it decides to do with that leverage will likely help determine the next chapter of Europe’s Greek bailout story.