I must have been 18-months-old, more or less, when he passed away in his sleep (along with my grandmother) due to a gas leak. A gas pipe had broken under the weight of an oncoming large vehicle which submerged the road outside their home.

A nice way to go, you’d say. To feel nothing. Not to suffer. To die in the arms of of your beloved. At 80 +. A full life.

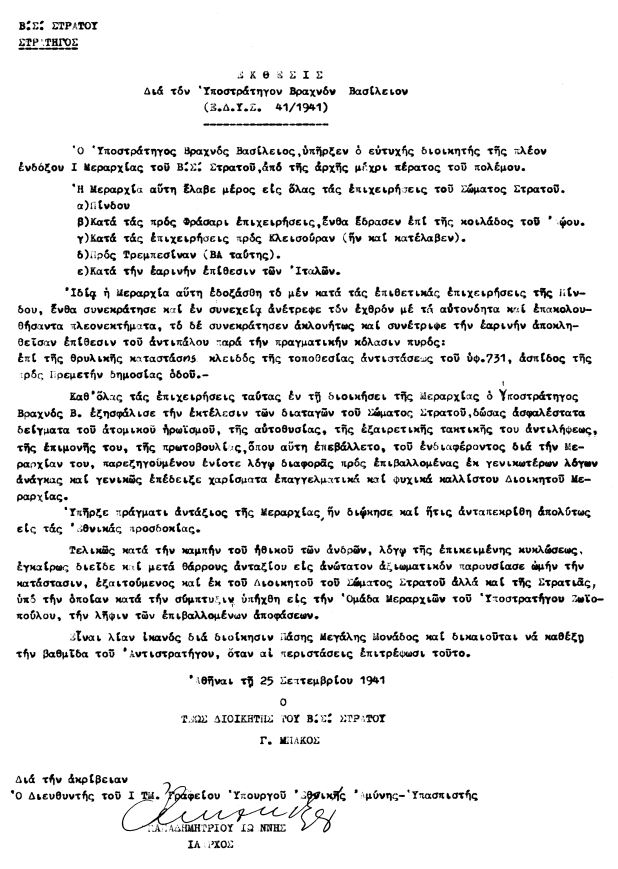

But, at the same, it was an ironic way to die. Especially if one considers that the same person emerged ‘intact’ and victorious from almost all the wars of the 20th century in which he was actively involved. So active, he was, deservedly, included in the pantheon of World War II heroes.

This is not the appropriate space to talk in detail. It is all written in Greece’s military annals in the blood of all those that sacrificed their lives without a second thought.

My aim is not to single out my grandfather’s contribution (because he is ‘mine’) in the struggle mounted by thousands of Greeks from the first moment the Greek-Italian war broke out- so many others have done so, at times distorting the truth (something not unusual, one might say. But these are hazardous habits).

He was a general. His position was on the frontline. From the first moment. He was destined, though (through circumstance, capabilities?) to link his name with some of the more glorious passages of modern Greek history.

I will not talk about the operation that pushed back the famous Julia light infantry division- the elite Alpini, specialising in mountain combat – at the outset of the war. This has been done by military academies that teach it (on an international level, if I’m not mistaken).

I will talk a little bit, though, about the ‘mother of all battles of the Greek-Italian war’ as it was named, that took place at an altitude of 731 metres-the Battle of Height 731.

Height 731 was a key position, 20kms north of Kleisoura in the central sector of Albania, which had been seized by the Greek army, during fighting the previous winter, and had pushed back the Italian troops, deep into the Albanian hinterland. But the Italians mounted a counter-offensive. And started regaining ground. However, if they were to break through the Greek front and march towards Athens, they had to take Height 731.

On March 9, 1941, in the presence of Benito Mussolini himself who arrived in Albania to get a close-up look at the operations (incensed after four months of war without victory against little Greece), Italy unleashed a huge airborne counter-offensive, the much- touted ‘Primavera Operation’. Its main aim was to break through a 6km stretch of the front in Glava at Boubesi.

The operation was undertaken by the 8th Italian Army Corps using four Divisions and two Blackshirts Battalions, while there were two more Italian Divisions in reserve. The 1st Greek Division of Larissa,which was pitted against them, had been fighting continuously since the outset of the war and, at the phase of the Italian counter-offensive, its mission was to keep the front intact.

Height 731 was defended by the valiant and determined Greek soldiers and officers of the 5th Regiment of the 1st Division, most of which were from Trikala and Karditsa. The Italians attacked Height 731 with intensity. Historical evidence testifies that the ferocious bombardment (from ground and air) transformed the landscape of the Height. Hand-to-hand close quarters combat ensued. Height 731 became drenched in blood.

On March 26, the outcome for the Italian army was tragic as it had been literally crushed on the Greek front. It was not just Height 731. It was an entire front. Twelve, rested and equipped, Italian Divisions fell on their faces against six fatigued Greek divisions, without gaining an inch of ground. Mussolini withdrew in disgrace, abandoning the dream to parade triumphantly through Athens.

My grandfather was there. Major General Vassos Vrachnos. As Commander of the 1st Division, he also assumed the responsibility of Height 731. That never fell. And it became a landmark. It is seen carved on the marble of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Of course it would not have been possible to achieve this on his own.

A general can only reach where his officers and soldiers can reach. But the general is always the one who creates and inspires loyalty and boosts the morale of the troops, even when the odds are stacked against them.

Even in the most difficult of times, the general is the one who always keeps an ace (or more) up his sleeve. And he weighs even the slightest detail to play his card at the right moment and come up trumps. Or lose the hand altogether and go down with the troops.

It’s just that in the Albanian mountains – a terrifying and natural defensive fort that put the lives of friends and foes to the test – it was not just one hand that was being played. It was the entire batch.

Unfortunately, victory did not last long. The humiliation of the rested and well-fed Italian troops by a handful of stubborn and heroic Greeks, forced Germany to attack Greece. This led our country to disaster. But as an event it had a fatal impact on the outcome of WWII because, in order to invade and conquer Greece, Germany expended select military forces and crucial time. It therefore postponed-longer than it expected – the final key campaign which would have completed the success of the Third Reich: The invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa).

However, as is well known, this time was lost in order to conquer little Greece and the Germans came up against an obstacle which they could never overcome: The Russian winter. This is where the German war machine completely froze-over. It was the beginning of the end of WWII…

Please pardon me if have have become tiresome. I return to the beginning.

I missed asking him:

“Hey grandad. What are (were) you made of?, What were you thinking of and, mainly, how were you thinking? Where did you find the strength? Why didn’t you leave everything to chance? Why didn’t you say ‘what the heck, I’m not going to change the world’? Why didn’t you look out just for yourself? How come you pushed on when others stopped, lost courage, deserted? Were you brave or just crazy?” (the same question is also addressed to everyone else that was there…)

I think he would have replied disarmingly, in a soft and steady tone: “I just did my duty”.

“Grandad…

Thankfully you’re not alive to see the mess we’re in

Thankfully you’re not alive to see how we are taught by commercials ‘how Greeks struggle’ and that ‘that’s how things are’.

Thankfully you’re not alive to see that there are Greek Nazis.

Thankfully you’re not alive to see how ashamed I am that I’m not like you.

Your grandson.

Christodoulos Papadimas”

The book ‘The action of the 1st Iron Division during the Greco-Italian war 1940-41’, based on the memoirs of General Vrachnos- Erodios publications – is out now. It is a ‘narration’ of military events, backed with military documents, orders, photographs, battle blueprints, bibliography and the honours bestowed upon the general.

The book’s editor is my father Vasileios Papadimas, himself a lieutenant general, the husband of the general’s only daughter, Angeliki Vrachnou. He had an unlimited admiration for his father-in-law and it was a life’s work for him to collect and compile the records of General Vrachnos and publish the TRUE story of the Greek-Italian war.

General Vassos Vrachnos, deputy Interior Minister, an MP from Argolida, a ‘son’ of Nafplion, became known to history as ‘The victor of Pindos’ but mainly as the leader of Greece’s military triumph against the intense Italian counter-offensive of 1941.

.