Since the murder of Pavlos Fyssas and the government crackdown on the Golden Dawn, people may have felt justified in thinking that the streets and public spaces in Greece are now clear of fascist intimidation. They would be wrong. Recent attacks show that the Golden Dawn is still active in the streets, while they are also moving towards the occupation of another public space, that of the Internet. Golden Dawners and their supporters are realizing the potential and logics of social media, and are increasingly seeking to incorporate them into their practices, albeit in a warped and perverse manner. Their expansion on platforms such as Facebook and YouTube is a significant development, but equally, if not more, noteworthy is their use of Facebook as a weapon against antifascist groups and pages. This is done in two ways: firstly, they mobilize their supporters to mass report antifascist pages to Facebook; and secondly, through setting up fake pages and circulating misinformation. These tactics, which would have made Goebbels proud, show the dubious and ambivalent role played by Facebook as a mediator, while they also signal a shift from thinking of social media as platforms for democratic participation and activism to understanding their more equivocal political role.

My concern with the relationship between the Golden Dawn and social media emerged out of a genuine question: does the Golden Dawn use social media, feted as vehicles for democracy precisely because of their networked, non-hierarchical, diffused and open architecture? If so, how does it reconcile this openness with its fascism? A first review of the Golden Dawn presence across social media showed that this consisted of a densely knit network of blogs and websites, revolving around the official Golden Dawn page (see Pic 1); a number of Facebook pages with a modest number of ‘likes’; a handful of Twitter accounts; and a more significant presence on YouTube. On the part of the organized and semi-organized Golden Dawn, YouTube appears to be the social medium of choice – this is clear in the number of channels tagged as Golden Dawn on YouTube, but it is also compatible with its internal logics of hierarchy and control. Twitter, on the other hand, is typically used to promote links to material posted on YouTube or affiliated blogs and websites. The contents of Golden Dawn-related materials on YouTube have aptly been described as microfascist but more broadly speaking, this preference for a broadcasting, one-to-many, style of communication is typical of the Golden Dawn, keeping it firmly in control even as it pretends to be outside of existing power structures and to represent the voice of the ‘common people’. In this manner, Golden Dawn’s ideas, rhetoric and discourses found an outlet in social media but without endorsing and following the logics of the many-to-many communication in social media.

Pic 1 Graph of the Golden Dawn online network (the numbers represent links received from the crawled population).

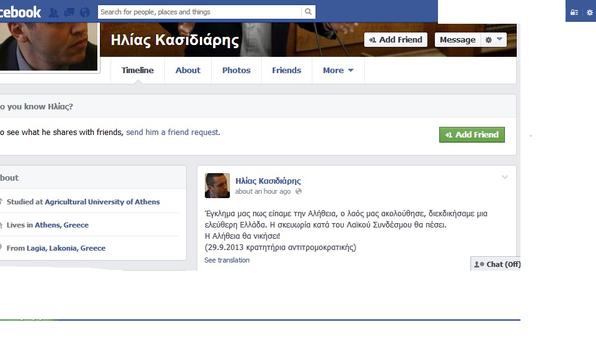

The question remains, however, why doesn’t the Golden Dawn have a more significant presence on Facebook? This lack must be attributed to the activism of antifascist groups as well as to Facebook’s terms of service. Following mass reports from users, Facebook has removed all pages of Golden Dawn MPs. This of course hasn’t stopped them: Ilias Kasidiaris, one of the highest profile Golden Dawn MPs, was posting messages while in custody (see Pic 2). Nevertheless, antifascist groups make use of Facebook’s terms of service, and especially clause 3.7 – “You will not post content that: is hate speech, threatening, or pornographic; incites violence; or contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence” – to report Golden Dawn-affiliated pages on Facebook. Despite new pages cropping up regularly, the constant vigilance of antifascist groups has succeeded in at least keeping them from building up momentum. This has resulted in a rather limited presence of Golden Dawn on Facebook, with most fascist/racist pages having a few hundred likes, and most Golden Dawn members taking cover in broader ‘patriotic’ pages.

Pic 2: Posting while in custody

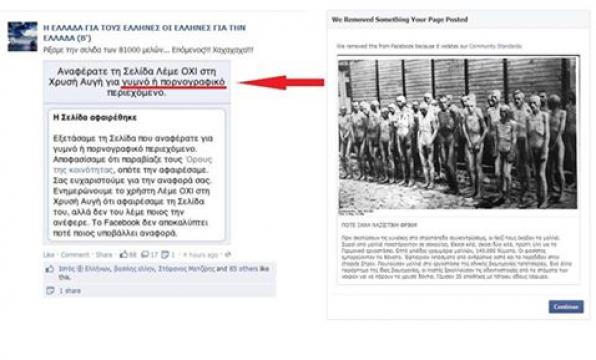

Yet in more recent months, things have started to change. Golden Dawn supporters have launched what appears to be an organized assault against high profile antifascist pages on Facebook, mass reporting them, and causing Facebook to take down pages either temporarily or permanently (see Pic 3). Making use of the same clause, they report antifascist pages for hate speech and nudity – this has led to the ridiculous situation of Facebook taking down posts criticizing the fascist practices and symbols used by the Golden Dawn, because they are depicting these symbols.

Pic 3: Calls to mass report antifascist pages.

In one occasion Facebook took down a picture of Holocaust victims because of nudity (see Pic 4).

These tactics have caused considerable disruption to the antifascist struggle, often forcing administrators to self-censor contents or to set up new pages duplicating contents.

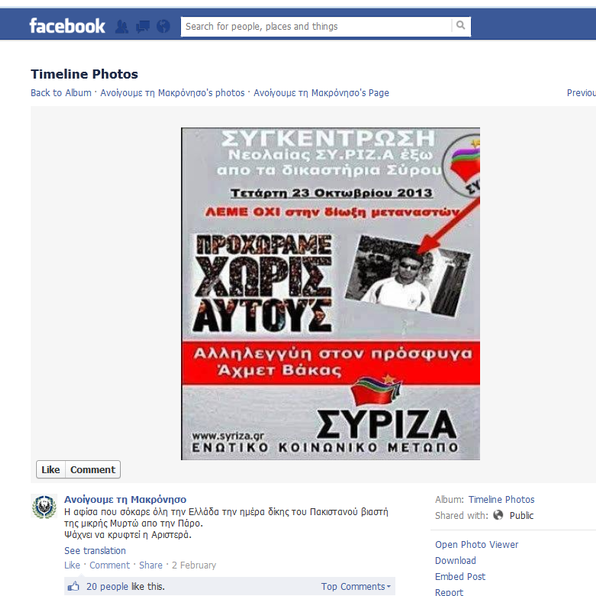

In a parallel tactic, Golden Dawn supporters set up their own pages, imitating the names, style and contents of antifascist pages, but planting false information and ‘news’, nationalistic arguments, baiting and disorienting users. As part of their broader misinformation tactics, they circulated a poster ostensibly made by Syriza and which called for ‘solidarity to the refugee Ahmed Vakas’, a convicted rapist (see Pic 5). While antifascist activists have repeatedly requested that Facebook take down these pages, the platform has not responded because it is not clear how they breech its terms of service.

Pic 5: Fake Syriza Poster

It is apparent that Golden Dawn and its supporters are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their use of social media platforms. Their tactics represent a mix of the good old propaganda practices pioneered by Goebbels alongside the logics of social media, whose diffused and networked architectures allow for the quick spread of information that cannot be immediately verified or easily removed. The emergence of Facebook as an arbiter in the antifa struggle in Greece is one of the most ambiguous developments: while Facebook’s strict adherence to the mainstream may be seen as preventing Golden Dawn pages from scaling, the ease by which Golden Dawners are ‘gaming’ its terms of service points to some of the problems that emerge by outsourcing public spaces to US-based corporations run for profit. But more importantly, this brief review shows the broader strategy of the Golden Dawn and its supporters to move and occupy more and more public spaces, to complement their intimidating presence in the streets with online harassment and intimidation.