Editor's note: This post continues TPPi's series of Yanis Varoufakis guest op-eds, originally published on his blog, yanisvaroufakis.eu

After the United States had lost its surpluses, some time in the late 1960s, the system of fixed exchange rates and highly regulated capital movements, which had nurtured capitalism’s Golden Age, was condemned. Its inevitable collapse could not but push the dollar down, release the bankers from their thirty-year-old restraints, and wind back rights and services that labour had wrestled from capital since the war.

Mrs Thatcher’s 1979 electoral victory was a pivotal moment in the post-Bretton Woods era. It marked a moment of truth when the establishment proved less (small ‘c’) conservative than the working class and the Left. Feeling its grip on power weakening, Britain’s bourgeoisie reluctantly, yet consciously, gave Mrs Thatcher the green light to swing her wrecking ball through the steel industry, the car and lorry factories, the coalmines, the shipyards; though each and every work site where the “enemy within”, i.e. organised labour, congregated. The Left’s reaction was to defend livelihoods by seeking to defend a business model that business itself had no longer any interest in. It is small wonder, therefore, that the Left was mightily defeated, as the threat to strike becomes pointless when the capitalist is no longer interested in… production.

The Thatcher governments were not responsible for the tidal change that swept Britain’s industrial model overboard. The decline was evident before 1979 and, as we have witnessed in continental Europe ever since, labour and industry were on a losing streak everywhere. However, what Mrs Thatcher did do was: (a) to create the ideology necessary to present de-industrialisation as a progressive, populist political project, (b) to nurture, foster and inflate a twin bubble (real estate and finance) that drove British capitalism at a time of industrial subsidence, and (c) to export her new-fangled ideology and her twin bubble to the rest of Europe.

Of course, Mrs Thatcher’s ‘contribution’ to European history would not have been possible had it not been for some strong undercurrents, quite independent of anything on the Iron Lady’s radar screen. The United States, under the far-sighted leadership of Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, was already turning itself into a gigantic vacuum cleaner, sucking into its territory both (i) the world’s net exports and (ii) most of the world’s capital (that was generated, in the form of profits, from exporting to the United States or to other lands because of the aggregate demand the United States was whipping up globally through its trade deficit). It was this astounding global recycling mechanism that provided Mrs Thatcher the tablet on which she would spell the end of British industry.[1]

Indeed, as Mrs Thatcher was settling in 10 Downing Street, a tsunami of capital was already beginning to flow from Japan, Germany, Holland, France, the oil producing countries (later from China) etc. to Wall Street, thus closing the recycling loop and financing America’s deficits. It took next to no time for City bankers, and their Tory associates, to work out a new business model for the UK: turn the City of London banks into a half-way station, linking the world’s net exporting nations with Wall Street. And ditch Britain’s own (trades union infested) industry.

Years later, in 2008, the pyramids of private money, that Wall Street and the City of London had built on the back of this constant tsunami of capital, crashed and burned. At first, continental Europeans smiled, allowing themselves an ‘I told you so’ moment, directed at the Anglo-saxons who had spent a decade or two sneering at the Continent’s antiquated commitment to manufacturing. Alas, that moment proved very brief. Soon, they realised that their own banks were replete with toxic assets and that their bankers had been allowed to run debts (or ‘leverage’) twice as great as those in the Anglo-sphere. Put simply, Mrs Thatcher bubble had been surreptitiously exported to Frankfurt, Paris, Rome, Madrid, Brussels etc. As had the ‘model’ of building up competitiveness by squeezing wages until the local economies, behind the glitzy suburbs and the globalised jet set, were in a permanent state of slow-burning recession.

Post-2008, while the United States and Britain sought to bailout the bankers with a combination of taxpayers’ money and quantitative easing that aggressively sought to re-inflated the deflated toxic assets, Europe was making a meal of the same project. Having rid themselves of their central banks, the Eurozone’s politicians did their utmost to shift all the stressed bank assets onto the shoulders of the weakest amongst the taxpayers, thus causing a horrid recession and putting the European Union on a path leading toward certain disintegration. Nevertheless, and despite the significant differences between Britain and the Eurozone, the broad picture remains the same: The establishment responded to the financial crisis by inflating bank and real estate assets (that were best left alone) and squeezing the majority of the population with soul and income sapping austerity. In short, the Thatcher model on steroids.

The Left’s Historic Duty

When Mrs Thatcher had to fight a ruthless class war on behalf of the ruling class, she had no qualms about destroying capital in order to ‘get’ labour and its organised expression. The Left did not realise this in good time and the result is today’s never-ending crisis. In the post-2008 world, capital is even less interested in value creation that it was between 1979 and the Lehman Brothers’ moment. As these lines are being written, we are witnessing a remarkable phenomenon: While the states are scraping the bottom of the barrel to make ends meet (i.e. to finance the public sector and to re-finance public debt) nearly $3 trillion of idle corporate savings are slushing around in the UK and in Europe, too frightened by low demand to be invested in productive processes and activities. Instead of investing in machines and skilled labour, corporations throughout Europe are using the cash to buy back their own shares in a bid to push up short-term share prices and the executives’ bonuses that are linked to the company’s share price. In conjunction with the terrible architecture of the Eurozone, which is keeping eighteen nations in the clasps of permanent debt-deflation, Europe’s labour and society remain moribund and at the mercy of far Right sirens.

Britain in particular can be legitimately called the Buyback Nation for, in addition to company share buy-backs, the Bank of England has been buying back public and private debt from the banks in a concerted effort to re-inflate Mrs Thatcher’s twin bubble. Put together, the Bank of England and the corporate sector’s buyback schemes amount to a large portion of Britain’s national income. And to what effect? To the effect of inflating house prices in the South (London primarily) and causing a fresh spate of debt-driven consumption that is leading Britain straight into the bosom of the next financial, economic and social meltdown. Meanwhile, as Mr Osborne is celebrating his shadowy ‘recovery’, industry remains threadbare and investment in capital goods is at an all time low.

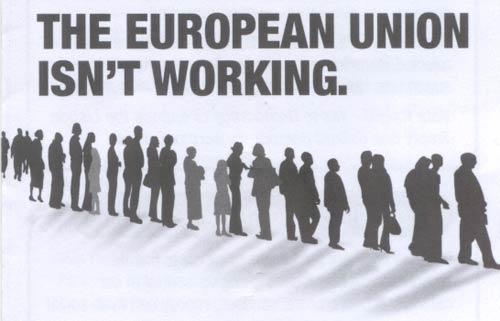

In short, unless the Left intervenes successfully, European societies will not recover. In 1979 Mrs Thatcher rode to victory on the back of the brilliant Saatchi and Saatchi slogan: ‘Labour isn’t working’. In 2014 we must turn the tables on the conservatives (both in Britain and in the European Union) with a similar slogan that makes people understand a simple truth: ‘Capital is no longer capable of, or interested in, value creation.’ So, it is labour’s historic duty to fill in the vacuum; to intervene politically so as to make value creation fashionable and possible again.

Toward a European Green New Deal

Growth is not the issue. The Left understands that there are many things whose growth must be stumped: toxic waste, toxic derivatives, ponzi finance, coal production, consumption that leaves the consumer unfulfilled and the planet worse for ware, etc. No, the issue is eclectic growth in the technologies and goods that contribute to a more successful life on a sustainable planet. The Left has always known that markets are terrible at providing these technologies and goods sustainably, and in a manner that sets prices at a level reflecting their value to humanity. What the Left was never very good at was in the conversion of that gut feeling into workable policy that the beneficiaries of this policy (i.e. the vast majority) would back.

To become relevant again, while Europe’s elites are sleepwalking into the next crisis, the Left must admit that we are just not ready to plug the chasm that a collapsing European capitalism will open up with a functioning socialist system; one that is capable of generating shared prosperity for the multitude. Presently, the crisis which began in 2008, and is metamorphosing into new socio-economic tensions throughout Europe, threatens to empower not the Left but the ultra Right. Exactly as the Great Depression did before. Our task should then be twofold: To present those who do not want to think of themselves as left-wing with an insightful analysis of the current state of play and to follow this sound analysis up with proposals for stabilising Europe – for ending the downward spiral that, in the end, reinforces only the bigots and incubates the serpent’s egg.

These proposals should constitute a European Green New Deal. Like the old New Deal proposed by Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, our European New Deal should include a credible plan for: (i) infrastructural investment; (ii) the notion of an across state borders (pan-European) welfare net; (iii) common public debt instruments and, last but certainly not least, (iv) a powerful manifesto threatening bankers with severe wing clipping. Unlike the old New Deal, Europe’s Green New Deal should also: (a) combine centralised funding for large scale green energy research projects with decentralised assistance to small outfits and cooperatives that create local, sustainable development in cities and in rural areas; (b) operate at a pan-European level without crushing national sovereignty; and (c) place a large part of the burden of implementation and financing on the European Investment Bank and the European Investment Fund, with substantial background support from the European Central Bank and the Bank of England.

Rehabilitating the state

One of Mrs Thatcher’s singular successes was the propagation of the belief that nothing good can ever come of democratically controlled agencies (or, more broadly, the state) while there are no limits to the wonders that the private sector is capable of. This was a remarkable achievement in the field of mischievous propaganda in a world where the computer, the transistor, space travel, the Internet, Wi-Fi, GPS, the touchscreen display of smartphones, and 75% of the most significant new drugs are the result of… publically funded research and development.

Apps and social media can be invented quickly and efficiently by the private sector only because the public sector has done the hard slog, over decades, of investing into long term innovation that requires steadfast financing that privateers would never, ever provide. As Mariana Mazzucatio has brilliantly exposed in her The Entrepreneurial State,[2] private, venture capital sits on the sidelines, while the public sector funds the basic research, and only springs into action when the breakthrough has been made, creaming the profits and sponsoring political attacks on the state’s ‘failure to innovate’, on its ‘crowding out effect’ on private investment etc.

Two are the charges against the state: its debt, that supposedly drags the private sector down, and its inability to innovate. Both charges are fraudulent and self-serving. Britain and the Eurozone are sporting an overbearing public debt only because the states had to clean up after the mess of private finance. And if the state’s innovative achievements have become fewer and further in between, it is because of thirty years of talking down the state, of depleting public research funding and institutions, of swinging a Thatcherite wrecking ball through the departments and institutes that could have kept Europe truly innovative.

The worst, and costliest, misconception of our era is that investment is an inverse function of taxation, wages and government involvement. While it is true that ceteris paribus investors prefer fewer taxes, lower wages and less red tape, other things are never equal and lower taxes, wages and government investment correlate strongly with unmotivated, de-skilled workers and lack of the R&D ecosystem which can uniquely nurture investment into seriously productive activities. The Left must, therefore, re-think the role that the state must place in funding the technologies of the future. Central to such a re-think must be our attitude toward banking and finance.

Putting the banking genie back in its bottle: Strategies for de-funding gambling and funding investment

A spectre is haunting Europe. It is the spectre of Bankruptocracy. A curious regime of rule by the bankrupt banks. A remarkable political arrangement in which the greatest extractive power (vis-à-vis other people’s income and achievements) lies in the hands of the bankers in control of the financial institutions with the largest ‘black holes’ on their asset books. It is a regime that quick-marches the majority of innocents into the trap of austerity-driven hardship that serves the guilty few, while Parliament and civil society are held at ransom. While 2008 was meant to raise ‘regulatory standards’, we now know that nothing of substance has been done to reform finance.

Governments in the UK and Europe are stuck in the false mindset that recovery will come through quantitative easing that reflates the value of dodgy assets (including anti-social house prices) and which fills up the banks’ coffers in the desperate hope that the bankers will then lend to innovative business. In short, Mrs Thatcher’s 1980s strategy (of squeezing labour and betting on bricks, mortar and the City) all over again. What the Left needs to do is to challenge this two-pronged fantasy in two ways: A new system of taxing and regulating banks and a renewed emphasis on public investment banking.

Taxing and regulating the banks

The current system of regulating and taxing the banks is absurdly contradictory. The state imposes minimum capitalisation and equity ratios. However, at the very same time, banks are offered tax breaks for relying on borrowed money in order to gamble. This absurdity results from taxing the banks’ profits. But when a bank borrows money to buy derivatives, its interest costs are deducted from its taxable income. As ‘bank profit’ is at best a dubious notion, the simple solution is to abolish corporate taxes on banks and replace them with a tax on their liabilities. In association with a hefty minimum equity requirement (of, say, 15% relative to their assets), the banking genie will be put back in the bottle, where it belongs.

Public green investment banking

Proper bank regulation will, whatever its other great social benefits, not reverse the dearth of investment in productive activities. International experience suggests that, to mobilise the mountains of idle savings, we need public investment banks staffed by specialists in the sectors that need to be developed.

One mistake the Left must not make again is to think that the solution lies entirely in the area of infrastructural projects. While building urban transport systems and investing in existing wave, solar and wind power generation technologies is important both for the environment and for short term job creation, the challenge must be grander: how to invest into transformative technologies. The recently departed Tony Benn once said that no general would halt a bombing raid because he was running over-budget. If that is so, it is ludicrous that our societies should not put together a new Manhattan Project, staffed with as many scientists as possible, with a brief to discover new forms of green energy, as opposed to developing the existing, primitive green technologies.

Funding such a Green Manhattan Project can only come from an ambitious vision of binding together Europe’s greatest achievement, the European Investment Bank (as well as its sister organisation the European Investment Fund, which already has a brief to fund small and medium sized firms in the area of urban renewal, technology and green energy), with our central banks (the ECB, the Bank of England, the Central Banks of Sweden, Denmark etc.). In our Modest Proposal for Resolving the Euro Crisis,[3] we have spelled out how this could happen. Put simply, why should quantitative easing be all about central bank money creation for the purposes of boosting government bond, real estate, and toxic derivative assets and not for the far more productive purpose of supporting the bond values of the European Investment Bank (EIB) and, potentially, a new British public investment bank that collaborates with the EIB? This would be Europe’s innovative answer to Brazil’s BNDS (which has recently invested more that $5 billion on clean technologies) or to China’s five year plan (2011-15) to invest $1.5 trillion (about 5% of China’s GDP) on green energy, biotechnology and zero emission cars.

Epilogue: Campaign for democracy, stabilise capitalism, re-imagine socialism

If Mrs Thatcher has a lesson for those of us on the Left, it is that progressive radicalism is the only antidote to regressive radicalism. For decades now we have allowed our ‘reasonableness’ to become the passive accomplice of a wholesale assault on rationality, development and propriety. During the 1976 Labour Party Conference, Tony Benn had warned: “We are paying a heavy political price for 20 years in which, as a party, we have played down our criticism of capitalism and soft-peddled our advocacy of socialism.” Tragically, in the following 20 years, since Benn’s prescient speech, European socialists lost the capacity even to distinguish capitalism from some, supposedly, neutral ‘market system’. Meanwhile, capitalism was busily at work undermining itself and paving the path to its own implosion in 2008. The time has now come for the Left to revive its critical perspective on capitalism and to plan for a future beyond it.

This is not to say that we are anywhere near ready to replace capitalism. Indeed, realism commands us to recognise that, if anything, Bankruptocracy is well and truly in command of the European continent and the only political forces on the march are those of the bigoted, ultra Right. The Left must not err again, as it did in the 1930s, thinking that capitalism’s great crisis will naturally lead to something better. It may very well bring about the most hideous dystopia. This is why it is of the essence to stabilise capitalism (through banking regulation, a link between central banks and public investment, and a wider social safety net) while struggling to revive democracy at the local, national and European levels. Our success in this limited but crucial goal is a prerequisite for forging a sustainable future in which most people are gainfully employed in innovative enterprises of which they are the sole shareholders.

[1] For a complete account of this global recycling mechanism, see Y. Varoufakis (2013). The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the World Economy, London and New York: Zed Books

[2] Mariana Mazzucato (2011). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking public vs private sector myths, London: Athem Press

[3] Yanis Varoufakis, Stuart Holland and James K. Galbraith (2013). ‘A Modest Proposal for Resolving the Euro Crisis, Version 4’