By Nikolas Leontopoulos

In a rational world, the revelations made by the ICΙJ regarding LuxLeaks, implicating Greek companies, would have prompted Greek authorities to take immediate action against the ‘network’: against all implicated companies and also against PwC, the company that set up the whole scheme.

In this world, the General Secretary of Public Revenue, the taxation officer that is preoccupied night and day with the collection of taxes, would now be (or more correctly would have long been) on a war footing against PwC.

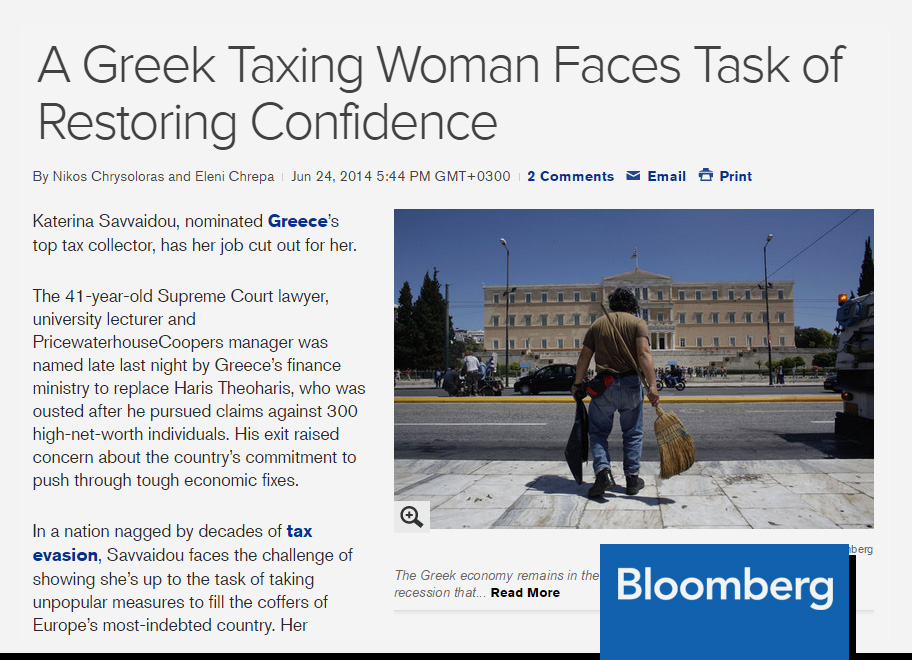

So let us visit the headquarters from where this war is supposedly being waged. Α stone’s throw from Syntagma Square, we meet Aikaterini Savvaidou, 41. She took over as general secretary of Public Revenue in June 2014.

Ms Savvaidou made it clear from the outset that her first priority would be tax avoidance. “Not to allow someone to tax evade. You can only succeed in doing this by closing all the loopholes of tax evasion (link in Greek),” she told close associates, according to To Vima newspaper.

There was undoubtedly a sense of irony in that statement, given that it came from a person specializing in… tax avoidance.

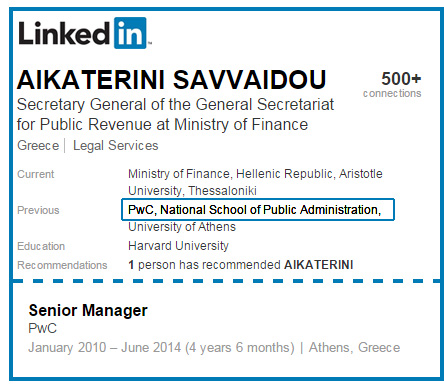

Up until June 2014, Ms Savvaidou was a senior executive at PwC, one of the so-called Big Four accounting firms of the world.

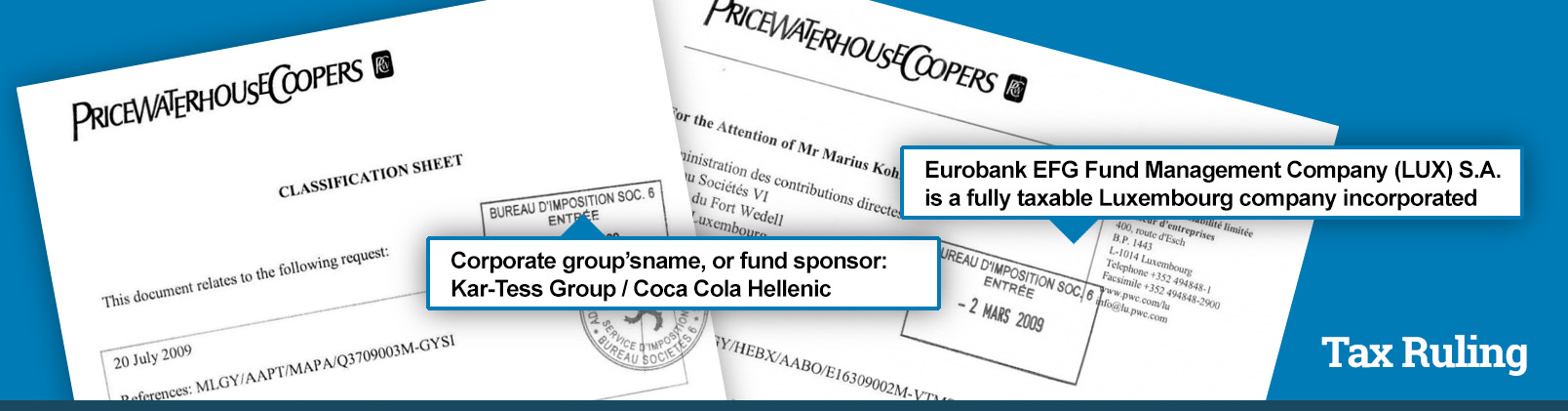

However, in the LuxLeaks case, PwC is the real protagonist. The company set up tax avoidance schemes, in collusion with Luxembourg authorities, for more than 340 multinationals. Among them are at least 9 companies associated with Greece.

Is it possible PwC's Senior Tax Manager ignored what PwC did?

Not only are Ms Savvaidou’s former links to PwC not a secret, but the finance ministry, in an announcement, made sure to stress that the new secretary was “currently a senior manager at PwC, Greece, responsible for a team of approximately one hundred lawyers and tax consultants. She is [was] also the Knowledge Manager of the entire organization of approximately 900 employees.”

According to the American-Hellenic Chamber of Commerce, Ms Savvaidou, as Tax Senior Manager of PwC is (still?) a member of the Chamber’s Tax Committee – a committee, which in its mission statement, makes clear that it will “not overlook any lawful, tax saving opportunities.” The same term («tax saving») is used by ICIJ in its key findings regarding Luxembourg’s tax rulings.

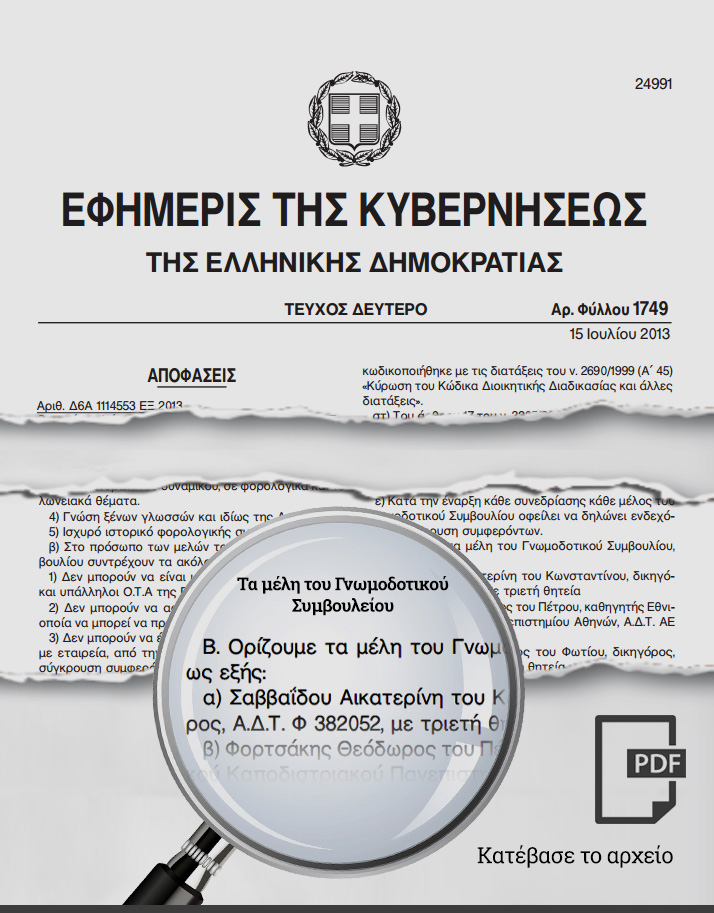

However, despite Ms. Savvaidou being a Tax Senior Manager at PwC, the Greek government had already appointed her in July 2013 (see graph) to a finance ministry committee and she made statements to the international media as ‘government advisor’ while (as we shall see below) still at PwC.

Her Linkedin profile states that she was a senior manager at PwC from January 2010 until June 2014, a period that overlaps with LuxLeaks.

For example, two of the tax rulings that allowed – according to ICIJ – Greek companies to avoid taxes (one ruling for the EFG Group of the Latsis Group, and one for Wind Hellas) are dated to February 2010 and March 2010, which is after the time Ms Savvaidou took over as senior manager at PwC.

In any case, Ms Savvaidou was an active manager at PwC when all these tax evasion schemes were in force: from 2010 to 2014.

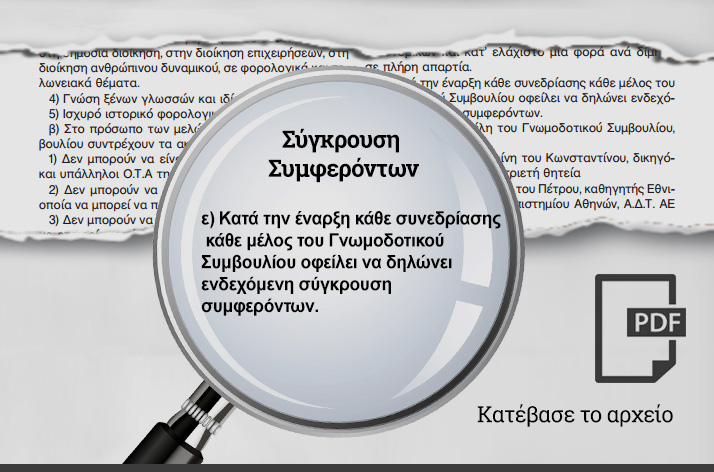

The Government Gazette, that officially announced her appointment to a Finance ministry committee in 2013 (while still working), made clear that “before the beginning of each session, all members of the Advisory Board are obliged to declare any conflict of interest.”

The Government Gazette, that officially announced her appointment to a Finance ministry committee in 2013 (while still working), made clear that “before the beginning of each session, all members of the Advisory Board are obliged to declare any conflict of interest.”

The question that begs an answer is the following: How is it possible that a ‘tax senior manager’, a ‘knowledge manager’, the head of the tax department of the company, did not know of the tax avoidance schemes that the company was setting up for a long list of companies?

Playing the devil’s advocate, one could argue that since the Greece-related companies implicated are domiciled in Luxembourg, why would PwC Greece get involved in the setting up of their tax schemes? However, most LuxLeaks tax rulings are about companies trying to move funds from Greece while at the same time avoiding taxes in the country. Furthermore, a great deal of these rulings concern business activities in Greece. How is it possible that PwC Greece was kept in the dark while the tax schemes concerned its own clients?

Coca-Cola HBC & EFG: Two serious cases of conflict of interest for PwC

The work of accounting firms can generally be divided into two contradictory activities: Auditing company books and to, as they themselves concede, help clients pay less tax.

Putting aside ethical concerns, is this legal? The accounting / auditing firms argue it is. However, according to statistics (source: Public Committee Accounts, House of Commons, pdf), the tax solutions they offer, when challenged in court, are deemed illegal at a rate of 50-75%.

A rudimentary rule of avoiding conflicts of interest is that the accounting firm does not interfere in the audit by providing advice on tax. (It may do one or the other, but not both with the same client, at the same time).

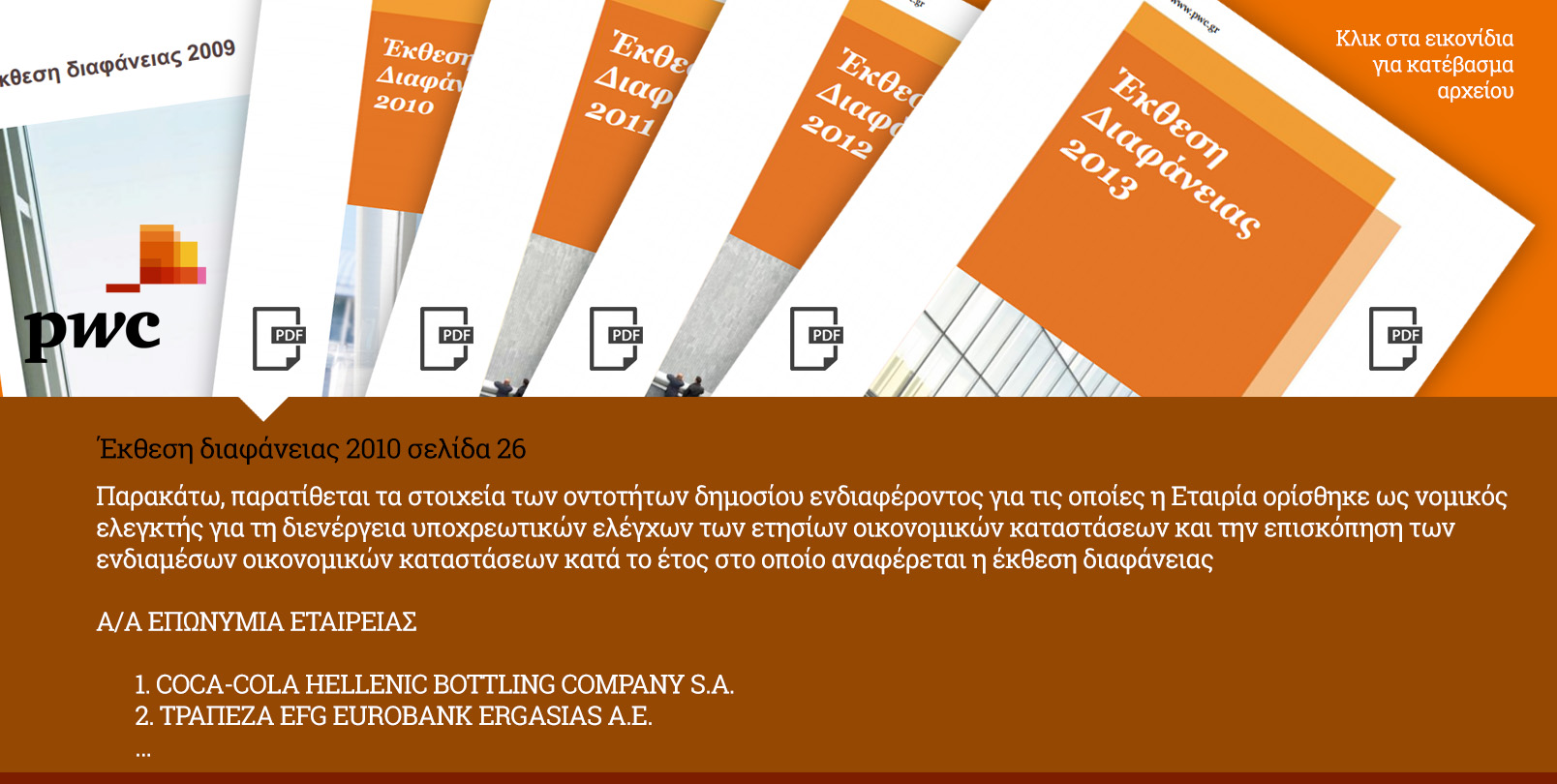

Cross-checking PwC’s own statements against LuxLeaks tax rulings shows that it did both. So, for the years 2009 and 2010, it secured tax rulings in Luxembourg for the EFG Group (Latsis Group) and Coca-Cola SBC (Leventis-David Group).

At the same time, according to the firm’s Transparency Reports for 2009 and 2010, PwC was “appointed as the legal auditor to conduct mandatory audits of the annual financial statements” for Coca-Cola SBC and Eurobank, the subsidiary of the EFG Group (see graph).

For many years, the Big Four had resisted legislation that would regulate and sanction conflicts of interests. But the Enron scandal in 2002 led to the famous Sarbanes-Oxley Act (or SOX from the initials of Senator Paul Sarbanes and congressman Oxley), which defined cases of conflicts of interest in the US.

But not in Europe, where similar initiatives were taken by the EU Commission and Michel Barnier only after 2011. The yet to be finalized ‘reform’ consists of a not so subtle compromise between Barnier’s initial plan and the accounting firms’ objections.

Access to the most guarded state secrets

The appointment of Ms Savvaidou beckons a difficult question:

Difficult not just to answer but even to pose: Holding the most important administrative position in the Greek tax collection mechanism, she has access to the most guarded state secrets. How compatible is it to appoint someone who, until recently, was the manager at a company whose interests are directly at odds with the interests of the Greek state?

But instead of these kinds of questions, the Greek media opted to provide information concerning Ms Savvaidou, from undisclosed sources within the finance ministry, such as the following:

“Most of the time, she wouldn’t even leave for her lunch break but would eat her salad (link in Greek) comprised of organic produce, which is her favourite, at the office, always taking care not to stain the papers on her desk”

.

Yet, a simple google search on PwC’s record would suffice. Let’s look at just once case.

British parliament MPs discovered in 2013 that the company had set up a transnational system with 7 levels so that the most expensive office complex in London, valued at 600 mln pounds (close to €1 bln), would not pay taxes on rent revenues.

The money would flow through the usual juncture i.e countries with PhDs in tax corruption. No, you are wrong to think of the PIGS – Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain. We’re talking about state-of-the-art-corruption here and not about receipts that a plumber or a tavern owner fails to provide.

The junctures used by PwC in its effort to conceal money weren’t on Mykonos, Naples or Barcelona, but in Luxembourg, Delaware (US) and Jersey (Britain)…

An international fan club for the General Secretary

There are countless such cases that demonstrate what PwC, and the Big Four in general, are doing. One didn’t have to wait for LuxLeaks to reveal it.

Nonetheless, when Ms Savvaidou’s appointment was announced for the position of General Secretary of Revenue, instead of disapproval, there was praise in Greece and abroad.

Three senior-ranking officials were vying for her appointment. All three, if we are to believe pro-government newspaper publications, were enthusiastic supporters.

First of all, she was proposed by Finance Minister Gikas Hardouvelis, according to the ministry’s official announcement.

Moreover, according to the To Vima newspaper, “a decisive role (link in Greek) was played by deputy Finance Minister Giorgos Mavraganis” who had a “successful [career] at KPMG”, one of the members of the Big Four club.

In other words, the battle against tax evasion in Greece is being waged by two senior executives at companies that specialize in… tax avoidance.

Finally, Ms Savvaidou would not have been appointed, if her choice had not been approved by the Inspector General of the Ministry of Finance of… France, Mr Petit, who, according to Proto Thema newspaper, participated in the 5-member selection committee that thoroughly vetted candidates (link in Greek). (So much for national sovereignty, if the Greek General Secretary of Revenue is approved by a Frenchman).

Bloomberg investigates tax evasion in “Greek nightclubs basements”

It was late spring in 2014, when ‘the Greek success story’ was, being propped up by both local and international media. Like any good drama with a happy end, it needed characters and heroes. And it found them.

According to Bloomberg, the new face of Greece was represented by two women: Aikaterini Savvaidou, the new general secretary of Public Revenue, and Anastasia Sakellariou, president of the Hellenic Financial Stability Facility.

According to Bloomberg, the new face of Greece was represented by two women: Aikaterini Savvaidou, the new general secretary of Public Revenue, and Anastasia Sakellariou, president of the Hellenic Financial Stability Facility.

(While in the case of Savvaidou Bloomberg thought it fit to bypass her tenure at PwC, it undermined the fact that Sakellariou was under prosecution for a felony committed in the exercise of her duties in her previous tenure at a bank).

Two months earlier, in April 2014 (before her new appointment), Savvaidou had talked to Bloomberg, in a story entitled Greek nightclub basements focus of tax evasion dragnets. The story focused on a ‘major’ issue: whether barmen give receipts to customers at night clubs.

Two months earlier, in April 2014 (before her new appointment), Savvaidou had talked to Bloomberg, in a story entitled Greek nightclub basements focus of tax evasion dragnets. The story focused on a ‘major’ issue: whether barmen give receipts to customers at night clubs.

Despite the fact that Savvaidou was still a senior manager at PwC, she made her comments in the story in her capacity as ‘government adviser”. How can one be a senior official at PwC and a government adviser at the same time?

The very same surrogates (in this case Bloomberg and Mr. Petit, as a representative of Greece’s troika of lenders) that for years rained fire on the country over endemic corruption and the Greeks, for not paying their taxes, were now praising a senior executive of a multinational company that specialises in tax avoidance.

Tangled: PwC and the Greek state

A counter-argument often put forth by those that supported Savvaidou’s appointment is that ‘it’s like hiring a hacker’.

The simile would work only on the condition that the one hiring the hacker (the finance ministry) and the hacker herself (Savvaidou), acknowledged that her previous employer was involved in wrong-doing.

We see no such acknowledgment. On the contrary, the Greek state never misses the opportunity to link up with accounting companies, and PwC in particular, to the point of ‘privatizing’ parts of its own authority.

- In 2009, even before the crisis began, the finance ministry, reportedly, put PwC in charge of the crackdown on small-time debtors at a time when, according to the ICIJ findings, the company was engaged in tax relief for its fat clients.

- In 2010, PwC was put in charge of controlling expenditure of the General Accounting Office – once more acquiring access to a sensitive domain of the state.

- In 2011, PwC was selected as an adviser for the privatisation of OSE/TRAINOSE railway transport service.

- Recently,on October 2014, finance minister Hardouvelis commissioned PwC to conduct a study on ways to amend the law concerning deferred tax of banks. According to pro-government news reports (link in Greek), the minister of Finance “completely sidelined the relevant ministry departments”.

He basically assigned the task of resolving an issue of national public interest to a private company which, by its very nature, colludes with Greek banks. And judging from the result, according at least to commentators such as Yanis Varoufakis and Klaus Kastner here and the Wall Street Journal here, the banks were excited with the solution.

A query for Mr Hardouvelis and Ms Savvaidou

Gikas Hardouvelis went to the finance ministry from Eurobank where he served for many years as a valuable associate of the Latsis Group. (Read the analysis by Yianis Varoufakis here about the conflict of interest entailed in serving these two posts.)

At the same time we saw how Ms Savvaidou ended up at a state post and how Hardouvelis supported her. Now it is revealed that Savvaidou’s former company (possibly with her collusion) devised a tax evasion scheme that benefited Mr Hardouvelis’s former mother company. The operation had many beneficiaries and just one victim: the Greek state, which Mr Hardouvelis and Ms Savvaidou now work for.

Isn’t there an ethical and political issue for both of them?

Illustration: Rania Papadopoulou