TPP joins refugee rescue mission in the Central Mediterranean: Every dot on the horizon could be a boat in danger

Rescue mission in the Central Mediterranean

Report/Video: Nektaria Psaraki

(English subs availiable)

Salvini’s blockades and the birth of Mediterranea

In 2018, when far-right politician Matteo Salvini became Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister, he launched a campaign to criminalise sea rescues under the pretext that rescue ships lacked Italian flags. This political pressure, combined with relentless media propaganda, forced many NGOs to withdraw, and several ships were seized. The historic IUVENTA, for instance, remains rotting in the port of Trapani. Its captain, Dariush Beigui, however, was undeterred despite being legally prosecuted. Today, he operates the rescue boat Abba1 as part of the Mare Jonio crew.

It was in this climate that activists Beppe Caccia and Luca Casarini took action. Both long-standing activists in social movements, from Occupy Social Centers to the 2001 Genoa protests, Caccia had also served as Venice’s Deputy Mayor for Social Affairs from 2001 to 2005. They launched Mediterranea, a platform that would bring rescue ships back to the sea, flying the Italian flag. Rooted in civil society and connected to social movements, Mare Jonio set sail in 2018, embarking on search-and-rescue operations amid increasing hostility.

The first missions were a leap into the unknown. With minimal resources—few volunteers, no radar, and limited experience—the team learned quickly, gaining strength as they went. By 2019, Greek rescuer Jason Apostolopoulos, who had experience from Lesvos to the Central Mediterranean, became the rescue coordinator for Mediterranea.

Breaking through Salvini’s barriers, the Mare Jonio consistently defied authorities by rescuing refugees and forcing entry into Italian ports, only to be charged each time. However, every investigation revealed the legality of their actions under international maritime and human rights laws, and they were repeatedly acquitted.

Today, Mediterranea Saving Humans continues its vital work, driven by the ethos of social movements and a commitment to humanitarian rescue. Their presence is felt in global crises, from aiding civilians in war-torn Ukraine to standing with the Palestinian people in Gaza and the West Bank. The Mare Jonio and its crew undertake self-organised rescue operations, filling the void left by state authorities that are either absent or, worse, complicit in preventing such missions.

A priest at sea: The Catholic Church’s involvement

Among the prominent figures aboard the Mare Jonio is Don Mattia Ferrari, a young Catholic priest and an early member of Mediterranea Saving Humans, whose steadfast support for the organization has sparked controversy, particularly among far-right groups They demanded explanations from the Church, only to be met with strong support from Pope Francis himself.

“If you are a believer, you have no choice but to help people in danger,” Ferrari said. He has briefed archbishops, senior clergy, and the Pope himself on the atrocities occurring in the Mediterranean, from the drowning of asylum seekers to the brutality they face in Libyan detention centres. His advocacy led the Catholic Church to launch a public awareness campaign on the refugee crisis, urging Christians to recognise the moral imperative of helping those in peril.

Ahead of Mare Jonio’s 18th search-and-rescue mission, Pope Francis personally sent his blessings to the crew.

TPP joins Mediterranea’s 18th rescue mission: On board the Mare Jonio

TPP, alongside journalists from Italian media, participated in the Mare Jonio‘s 18th search and rescue mission, led by mission chief Beppe Caccia and rescue coordinator Jason Apostolopoulos.

The operation began at the port of Trapani, Sicily.

Seeing the Mare Jonio for the first time, one can’t help but recall the hollow excuses of the Greek Coast Guard when defending its actions against asylum seekers. “We couldn’t get close, there were too many migrants, any move of ours could have put them in danger,” were among the justifications given after the Pylos shipwreck, involving the advanced PPLS 920—the so-called “pride of the Coast Guard.” In stark contrast, the Mare Jonio is a 1970s vessel, modest and unassuming, with a crew of just 12—six sailors and six rescuers—who save hundreds of refugees and migrants not because they’re equipped with cutting-edge technology, but because they can, and because they choose to.

The Mare Jonio is equipped with 1,000 life jackets, two inflatable rescue boats, and life rafts. Before a shooting attack by the so-called “Libyan Coast Guard,” it also carried two Centi Floats—long inflatable cylinders, nicknamed “bananas,” designed to help castaways stay afloat by gripping onto handles. Now, only one remains.

“The Hellenic Coast Guard doesn’t even equip its ships with life jackets because its primary focus is not rescue, but prevention,” Jason Apostolopoulos told TPP.

In contrast, the Mare Jonio is equipped with a fully stocked pharmacy, carrying essential medicines like pain relievers, ibuprofen, antibiotics, paracetamol, and treatments for nausea, diarrhoea, skin conditions, and burns. It also has a range of first aid supplies to enable the crew’s doctor and nurse to treat refugees in need of medical care. Additionally, the organisation includes a volunteer midwife, recognising that many pregnant women often embark on the perilous refugee journey. During this mission, we learned that a 9-month pregnant woman, who had been on a refugee boat, successfully reached Lampedusa and gave birth to her baby girl on the pier.

How to rescue hundreds of refugees at sea: Step one, it’s possible

Before every mission, the crew undergoes both practical and theoretical training led by rescue coordinator Jason Apostolopoulos. TPP had the opportunity to observe and document the process.

Rule one: Never dive into the sea

“Our top priority,” explained Apostolopoulos during the training, “is our own safety. If we’re not safe, we can’t help anyone else. So, the first rule is: never jump into the sea. I’ve worked as a lifeguard in Greece, and every lifeguard knows that when a drowning person sees both a life jacket and another person, they’ll instinctively grab the person. That’s the survival instinct kicking in. In that moment, the drowning person’s adrenaline is through the roof, and they’re much stronger than usual. That’s why we don’t send in lifeguards as swimmers. We use rescue boats to conduct the rescues.”

Once a boat is spotted, Mare Jonio stops about 1 to 2 miles away

Apostolopoulos continued: “When we identify a refugee boat, we must stop the Mare Jonio in time—within a mile or two if the boat is moving quickly. It’s crucial not to let the refugees approach the Mare Jonio because if they do, their boat might crash, capsize, and lead to fatalities. We then lower the lifeboats, Abba 1 (which holds 20-25 people) and Abba 2 (which holds up to 10), each equipped with four life jackets, and they go together. The reason is that the approach phase is the most dangerous part of the rescue. Most shipwrecks happen at this point. These people have endured torture and imprisonment in Libya, travelled for days without food or water, and when they finally see safety, they become agitated. They stand up, they move, and that can destabilise their boat.”

The two main causes of death: crushing or drowning

Apostolopoulos explained that deaths at sea typically come from two causes: crushing or drowning. “When we say ‘crushing,’ we mean the refugees get crushed inside the boat. Overcrowded inflatable boats, carrying 100 to 150 people—180 at the most, in my experience—tend to crack in the middle, trapping refugees inside. Most deaths I’ve witnessed occurred inside these boats. To conduct a successful rescue, we need to understand the ‘magnet effect.’ Rescue boats act like magnets—wherever we position them, the refugees will instinctively follow. This can be either helpful or dangerous. An experienced rescuer knows how to draw attention to the safe area, but if you approach the damaged part of the boat first, you’ll guide everyone right into the danger zone,” Apostolopoulos explained.

During the approach phase, only one person speaks

The approach phase of a rescue resembles a carefully orchestrated performance. As Abba 1 and Abba 2 move closer to the refugee boat, only one person—typically the rescue coordinator, in this case Jason Apostolopoulos—speaks. If it’s night, all the lights focus on him, while the rest of the crew stays in the background. He doesn’t wave, smile, or greet anyone. If the refugees start to get distracted or look towards other faces, the crew subtly directs their attention back to the coordinator. “It’s crucial that only one person speaks,” explains Apostolopoulos. “Confusion causes panic, and panic can be deadly.”

If everyone isn’t seated before life jackets are handed out, we back off as many times as needed

This part of the rescue is called “Sending the Message.” As the rescue boat nears the target, the coordinator raises his hand in a firm salute and greets the refugees.

“Hello, how are you? We are an Italian rescue boat, and we’re here to help. What language do you speak? Does anyone speak English or French?” Apostolopoulos says.

“It’s vital to explain who we are. These people have been at sea for days, and the sight of a ship can trigger fear or hope. We could be anyone, even Libyan, and we’ve had refugees flee from us in panic. Establishing trust is essential before we begin the rescue.

Next comes the panic control phase,” he continues. “We instruct everyone to sit down and stay calm. Once they’re seated, I remove my helmet and demonstrate how to wear a life jacket step by step. Then we distribute them, starting with the most vulnerable—babies and children.”

Jason Apostolopoulos stresses: “If the refugees start standing up as we hand out life jackets, we immediately back off and I shout for them to sit down. We repeat this as many times as necessary until they understand that if they don’t sit, the rescue won’t begin. It’s crucial to ensure everyone’s safety.” Once everyone is seated, they are lifted into the rescue boat, Abba 1, one by one. “When it’s full, with about 20-25 people, we transfer them to the Mare Jonio,” he explains.

We spray on the empty boat that we abandon in the Mediterranean: SAR – Date

After completing the rescue and transferring all refugees to the Mare Jonio, the crew spray-paints “SAR” (Searched and Rescued) along with the date on the abandoned refugee boat. This ensures that anyone encountering the empty vessel knows its passengers were rescued.

The Italian Coast Guard is then notified and decides whether to pick up the refugees, allowing the Mare Jonio to continue its mission. If not, the rescue ship itself transports them to safety. During this process, the refugees are registered, examined by a doctor, provided with medical care, given food, water, and clean clothes, and offered the chance to bathe.

The searching procedure

Mare Jonio operates in international waters, often reaching its target after almost 24 hours at sea. On this particular mission, it sailed as far as eight hours from the Libyan coast and 28 hours from Sicily, covering areas within Italy, Malta, Tunisia, and Libya’s rescue responsibility zones.

The search process involves radar, constant monitoring of rescue channels on radios, visual searches with binoculars, and assistance from a rescue sailboat and the Colibri 2 rescue plane, operated by volunteer pilots.

Observing the rescuers scanning the sea with binoculars, one might question the odds of spotting boats in distress amidst the vastness of the Central Mediterranean. Yet the results are striking. The favourable weather conditions in the region provided an ideal opportunity for dozens of boats to set sail from Libya and Tunisia.

Every time a small dot appeared on the horizon, it was a refugee boat. Either empty, with the Italian coast guard having performed a rescue, or overloaded with refugees.

First rescue: 62 refugees, including 16 women and 15 small children

On August 24, 2024, at approximately 17:00, the Colibri 2 rescue aircraft spotted an overcrowded wooden boat carrying dozens of refugees. Rescue boats Abba 1 and Abba 2, fully stocked with life preservers, were dispatched to the location. Upon arrival, they encountered 67 refugees on board, including 16 women and about 15 small children, many of them toddlers or infants. Unlike in Western societies, adolescent refugee minors often don’t consider themselves children.

The refugees had been at sea for about three days and were disoriented. The boat was so heavily loaded that passengers’ legs dangled over the sides. It was in poor condition, listing to one side. When the refugees heard Jason Apostolopoulos call out from a distance, assuring them they were approaching an Italian rescue ship, they responded with shouts of relief and celebration.

The rescue operation, as shown in the TPP video, followed the training protocol to the letter. The rescuers first established trust with the refugees, assessed the boat’s condition, and then systematically distributed life jackets, ensuring each step was carried out safely and efficiently.

Suddenly, the mission leader, Beppe Caccia, is heard over the radio, alerting the team that a speedboat is rapidly approaching. It was the Italian Coast Guard, responding to the distress signal they had received.

“The so-called Libyan Coast Guard,” explains Jason Apostolopoulos, “are essentially armed militias, financially and logistically backed by Italy and the EU, tasked with keeping refugees in Libya and preventing them from reaching Europe.” He highlights the grim reality: “These forces return refugees to Libya, where they face slave markets, torture, kidnappings, and imprisonment in private makeshift prisons, with their families extorted for ransom. Refugees have told us, on more than one occasion, that if they were to be returned to Libya, they would rather drown.”

When a refugee boat enters Italian waters of rescue responsibility, the Italian Coast Guard typically intervenes to conduct the rescue and transport refugees to safety.

That’s what happened in this case too. The rescue boat of the Italian Coast Guard arrived on the scene and took the refugees—albeit somewhat rudely, in relation to the volunteer rescuers—to the deck, which already had other refugees from a previous rescue. The TPP did not manage to secure much footage of the Italian Coast Guard operation because, as you can hear in the video, the captain shouted “no photos” as soon as he saw the TPP lens pointed at the Coast Guard ship. Despite the fact that it was an arbitrary request, the TPP obeyed the instructions of the rescuers, so that the company would not be endangered by any kind of tension or arbitrariness of the authorities. Coastguards then loaded Mediterannea’s life jackets onto the refugee boat instead of returning them to rescuers, despite repeated pleas.

This gave us the chance to closely examine the empty refugee boat. As shown in the TPP video, its surface was entirely flat, which explains why the refugees’ legs were dangling over the sides. Approaching the boat, the strong smell of spilled gasoline became evident, with jerrycans strewn inside and parts of the boat flooded. The boat’s poor condition was striking, though sadly, not uncommon.

The boats departing from Libya are mostly makeshift—either wooden or inflatable. Mare Jonio rescuers explained to TPP that, due to the confinement of refugees in Libya as stipulated by the Pact, the production of small, regular boats seems to have ceased. Recently, a new type of boat has emerged, especially in arrivals from Tunisia. These iron boats are cobbled together from various metal pieces and feature long, pointed bows, complicating the rescue process as their sharp edges often puncture the inflatable lifeboats during contact.

Second rescue: 50 Africans, 43 minors—From Libyan slave markets to safety

The Mare Jonio pressed on. By 11:00 PM that same day, only hours after the first rescue, a fisherman spotted an overloaded inflatable boat carrying African refugees. He immediately sent out an SOS on VHF channel 16, and the Mare Jonio responded, heading to the location. The pitch-black night made the search and rescue process incredibly challenging, as the ghostly outline of the boat could be just a few metres away but remain unseen.

The Mare Jonio signalled by flashing its lights three times into the darkness. Suddenly, a faint, distant light responded with three flashes—the boat had been located. Rescue boats Abba 1 and Abba 2 approached and discovered an inflatable raft carrying 50 refugees, 47 from Ethiopia and 3 from Sudan, many of them severely exhausted. Among them were 43 minors. Over the radio, Beppe Caccia relayed that they were awaiting approval from the Italian Coast Guard to begin the rescue operation. However, assessing the boat’s dire condition—visibly splitting from the strain of overloading—Jason Apostolopoulos made the urgent call to proceed with the rescue immediately. There was no time to wait; lives were at stake.

This rescue was starkly different from the one earlier that afternoon. There was no laughter or celebration, only silence. The refugees were visibly terrified and deeply distressed. Many of the African refugees had endured unimaginable horrors in Libya, where they were sold into slave markets and forced into brutal manual labour. Subjected to daily physical abuse, they lived in deplorable conditions. Often, they were sold multiple times throughout their ordeal. Kidnapped by gangs, they were held in private prisons, trapped in a never-ending nightmare of exploitation and violence.

Ibrahim Lo recognises his own story in the faces of persecuted Africans

Originally from Senegal, Ibrahim Lo was just 16 when Jason Apostolopoulos rescued him. Today, he is an activist and author of the book Pane e Acqua (“Bread and Water”), which inspired the film Io Capitano. Lo now works as a parliamentary assistant to Italian Left MEP Domenico Lucano.

In his interview with TPP, Ibrahim shared the harrowing details of his journey. After trekking through the Sahara Desert for nine days to escape to Europe, he found himself trapped in the same makeshift prisons and slave markets that still exist in Libya today.

Upon arriving in Libya, Ibrahim was kidnapped and crammed into the trunk of a car with other migrants. After hours in the suffocating heat, he was barely able to stand when they finally released him. They beat him, giving him only bread and water—an event that later inspired the title of his book. Held as a slave for ransom, he witnessed the brutal deaths of three fellow prisoners—two from the Gambia and one from Nigeria—who were killed after trying to escape.

“They beat them to death with the handle of a Kalashnikov, then shot them to finish them off,” he recounted. The Libyans then tortured the rest of the captives to set an example. Ibrahim was hung upside down and beaten, leaving scars that are still visible today.

Eventually, Ibrahim boarded a flimsy inflatable boat to escape Libya, but the journey ended in a shipwreck that claimed several lives. The boat began to take on water, and in that moment, Ibrahim feared the Libyans would find them and drag them back to the horrors they had fled. But just in time, Jason Apostolopoulos and his rescue boat appeared, saving Ibrahim and dozens of others from their terrifying ordeal.

Today, Ibrahim is deeply involved in activism and writing, and is a member of various anti-war movements. He was also aboard the Mare Jonio during its rescue mission, where he assisted in saving others—once a refugee himself, now helping those in need.

When Ibrahim saw the 50 African migrants, he couldn’t contain his emotion. After receiving medical care and support aboard the Mare Jonio, the Italian Coast Guard transferred the migrants to Italy in the early hours of August 25.

The inflatable boat they had used, filled with makeshift black coils in a desperate attempt to stay afloat, now drifts abandoned in the Central Mediterranean. It bears the markings SAR – 24/08/2024, a silent testament to their rescue.

Third rescue: 67 refugees, 5 minors – Many had been tortured and kidnapped in Libya for ransom

At dawn, as the first rays of sunlight broke through, the Mare Jonio rescuers spotted a refugee boat approaching the rescue ship. Just hours after completing the second rescue, a new operation was underway.

This time, the refugees themselves sought out help, signalling their distress. The rescuers swiftly lowered the lifeboats and approached the scene. It was another overcrowded vessel, carrying 67 refugees from Syria, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, including five minors. Upon realising that the rescue ship was coming to their aid, the refugees erupted into cheers of joy and relief.

In this particular rescue, The Press Project is unable to publish extensive images as many refugees did not consent to being photographed. Some had only recently escaped from their captors and feared being tracked, while others had sensitive backgrounds, including a judge, a lawyer, war refugees, and individuals persecuted by the Assad regime in Syria.

Abductions and torture in Libya

As the refugees boarded the rescue boats, they shook hands with the crew and kissed the helmets of the rescuers. Their first words were filled with fear: “Libya no good.” Once aboard the Mare Jonio, their relief was palpable.

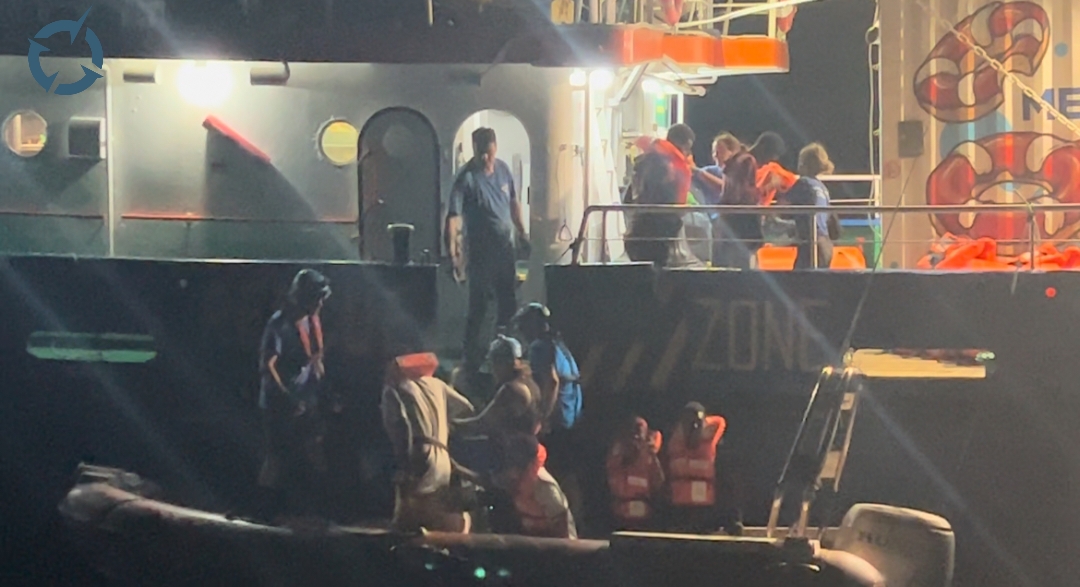

Refugees boarding the Mare Jonio. Credit: Nektaria Psaraki / The Press Project

One refugee from Bangladesh shared his harrowing story with TPP. Upon arriving in Libya, he was kidnapped for a ransom of €20,000—an impossible sum for his family. “They had to sell my father’s land in Bangladesh to pay for my release. Our home was sold for €9,000, and my family struggled to raise the remaining €11,000,” he explained.

Another refugee from Syria recounted his abduction: “I was on my way to eat when a car stopped beside me. Four men got out, kidnapped me, and took me to a place that looked like a prison but actually wasn’t. In Libya, anyone with a gun is a policeman. Anyone without a gun isn’t. They beat me,” he said, showing t

______________________________________________

Are you seeking news from Greece presented from a progressive, non-mainstream perspective? Subscribe monthly or annually to support TPP International in delivering independent reporting in English. Don’t let Greek progressive voices fade.

Make sure to reference “TPP International” and your order number as the reason for payment.ζ

he scars on his hands. “They demanded €1,000 from my family. We paid them, and they let me go. I was terrified it would happen again, so I fled as soon as I could.”

A 15-year-old Syrian also shared his story: “They kidnapped me too, but I told them I was young and had no money. When they learned I was 15, they let me go. I spent one day in captivity, but they didn’t beat me.”

Each time the TPP camera was turned on, one refugee would hide his face. We asked why. “I’m a judge,” he said. “I fled Syria with a lawyer friend. They are hunting me. If they see me, they will find me and kill me. My family is also in danger.”

Unlike earlier rescues, the Italian coast guard did not arrive this time, and Malta ignored every call and distress signal. As a result, the Mare Jonio had to take a 28-hour return journey with the refugees on board. Along the way, the rescued passengers, now smiling and grateful, shook hands with the crew, thanking them for bringing them to safety and offering a chance to rebuild their lives and reunite with their families.

The refugees disembarked at the Sicilian port of Pozzalo, marking the end of a 14-hour mission in which the Mare Jonio rescued 182 people. In a region where state mechanisms are often absent, and EU member states strike controversial deals with African governments that leave countless lives at risk, civil society has stepped in to fill the void.

As governments peddle propaganda about “suspect NGOs” and brand rescue workers as “traitors” or “slanderers,” Europe’s political landscape grows ever more conservative. Yet, while the rhetoric of exclusion intensifies, self-organized rescue missions continue to save lives in the world’s deadliest migration route—the Central Mediterranean. In 2024 alone, 1,320 recorded deaths underscore the human cost of inaction.

Against this grim backdrop, Mediterranea Saving Humans has rescued 1,500 people and counting. Undeterred by obstacles, the organisation is already preparing for its 19th search and rescue operation, proving that solidarity and humanity endure even in the face of hostility and indifference.

______________________________________________

Are you seeking news from Greece presented from a progressive, non-mainstream perspective? Subscribe monthly or annually to support TPP International in delivering independent reporting in English. Don’t let Greek progressive voices fade.

Make sure to reference “TPP International” and your order number as the reason for payment.