When in 2010, visual artist Tassos Triandafyllou visited the monastery of Zoodochos Pege, Baloukli in Istanbul with a group of high school students, he found himself suddenly drawn to a cluster of tombstones. Originally they adorned graves in the Greek precincts of the surrounding cemeteries. Today, the graves are gone, but the monuments have been preserved and pave the courtyard of the monastery and, with their inscriptions, provide a window into the lives of Greeks living two centuries ago in the city.

Mr Triandafyllou, a visual artist who produces works using, among others, the technique of frottage – or producing an imprint of a surface by tracing over it repeatedly with a substance such as graphite – sought and was granted permission by the Patriarchate to produce imprints of the funerary monuments. 15 such works are now on display in the exhibition ‘Identities – Baloukli and the Romioi (Greeks) in Constantinople, 19th century.

Watch a video of the process:

The works are both modern yet comprise literal imprints of the past. They are presented together with other artifacts such as icons, books and engravings from the thriving Greek (Romioi) community in Istanbul in the 19th century, thus placing them in the appropriate socio-political context.

The inscriptions on each of the plaques are short, but provide a window into the lives of those who lived generations ago in the Byzantine and Ottoman capital. Some are in Greek while others are written in ‘Karamanli’ writing – ie Turkish written in Greek script. Furthermore many of the plaques bear symbols which signify the trade of the deceased. On the grave of a grocer scales are inscribed, while the grave of a midwife depicts what appears to be a birthing stool.

“The material evidence from the collections of the Byzantine Museum come into a dialogue with the work of Tassos Triandafyllou which in this exhibition acquires a documentary dimension and with the information that it provides serves as a catalyst in the rereading of our collections,” writes Dr Anastasia Lazaridou, Director of the Museum. The exhibition will run until the 27th of April.

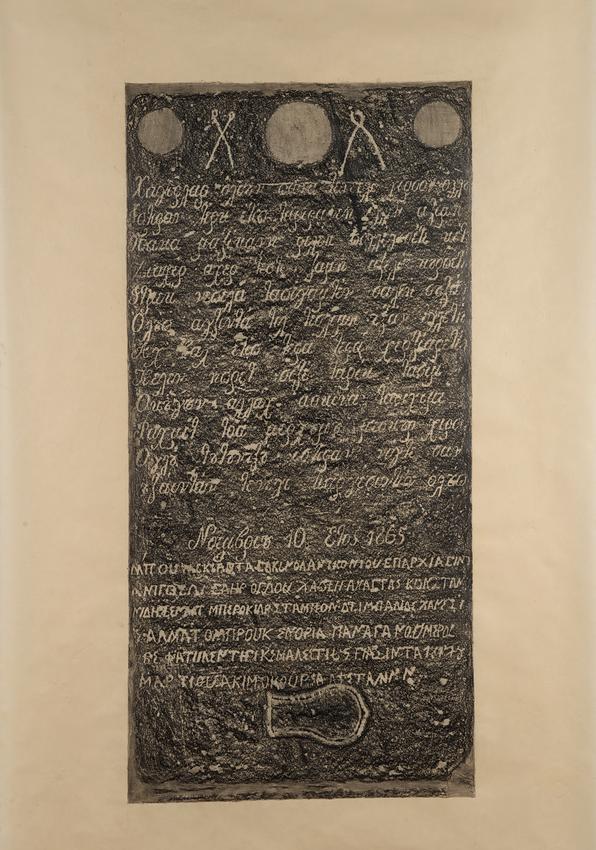

Below are some of the imprints of the plaques and their translations:

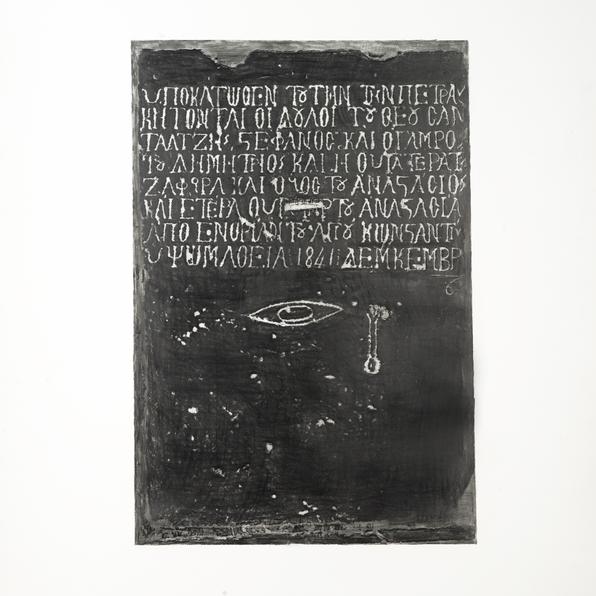

1. “Here lives the servant of God Kyriake the wife of Kosmas from the parish Metohi, 1841”

2. September 8 183… Gravestone of a pilgrim from the parish of Hagios Theodoros “Frakas”. He was probably a peddler or gardener – the mark is reminiscent of a gardener’s mattock while in Vlanga there were many gardeners.

3.”Under this plaque lie the servants of God Santaltzis Stefanos and his son in law Demetrios and his daughter Zafeira and his son Anastasios and his other daughter Anastasia from the parish of Hagios Konstantinos in Psomatheia 1841, December 6.” The word “Santaltzis” probably refers to the profession of sandal maker or to that of a boatman – the engraved mark could depict a boat with a boat paddle.

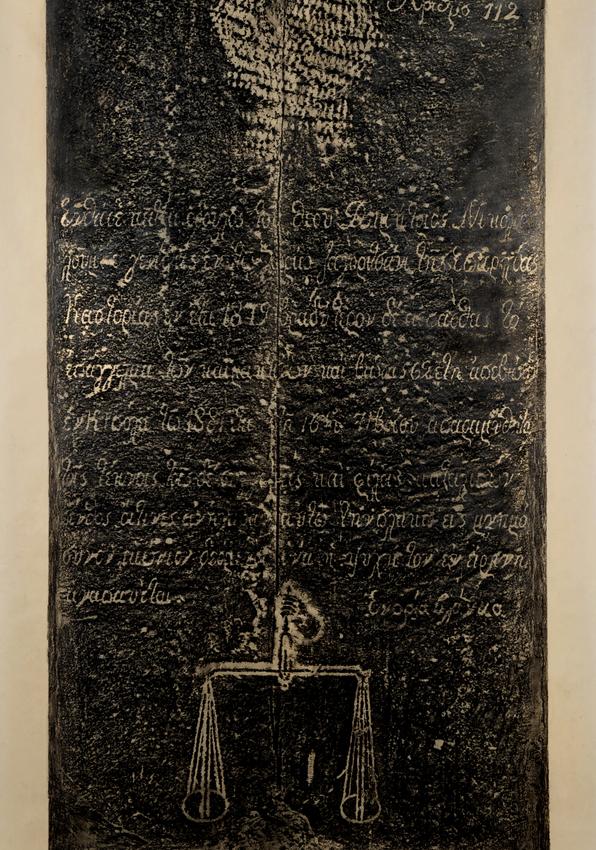

4. January 20, Gravestone of the midwife Anastasia, wife of the peddler Chatzis Nikolaos. It bears a request to the brethren Christians to “give appropriate forgiveness”. At the bottom, a mark that could depict a stool or a couch that was used during gynecological examinations or childbirth.

5. July 15 1838 GRavestone of Andreas, a coppersmith

6. 184(9?) February 2. “Here lies the servant of God Georgios, son of Yiannis from the Village Chotzitsa of the province of Korytsa, cook at Ounkapan”

7. Graveston of the milkman Demetrios Nikolaou who was born in 1819 in the village of Zagoritsani of Kastoria and died in Constantinople when he was 62. At the bottom the engraved mark of a scale.

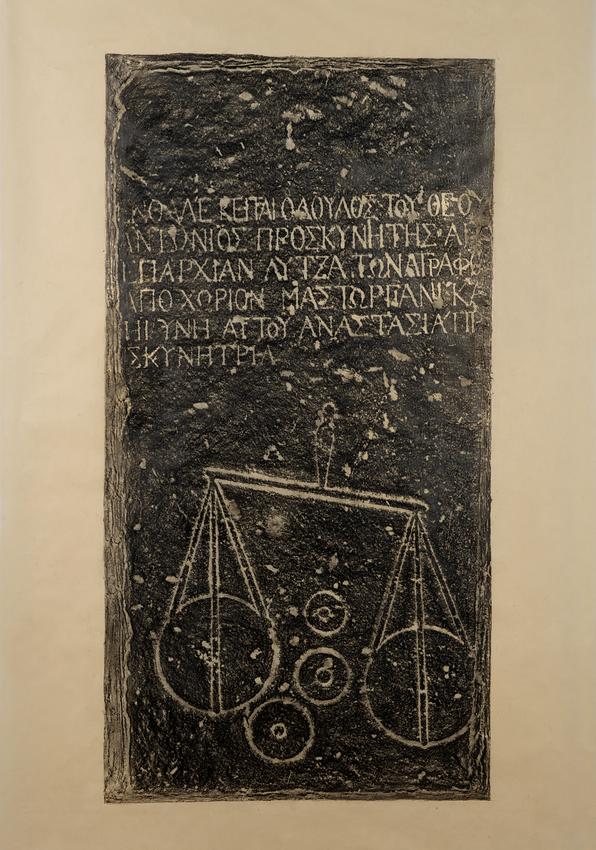

8. Gravestone of a grocer Antonios and his wife Anastasia

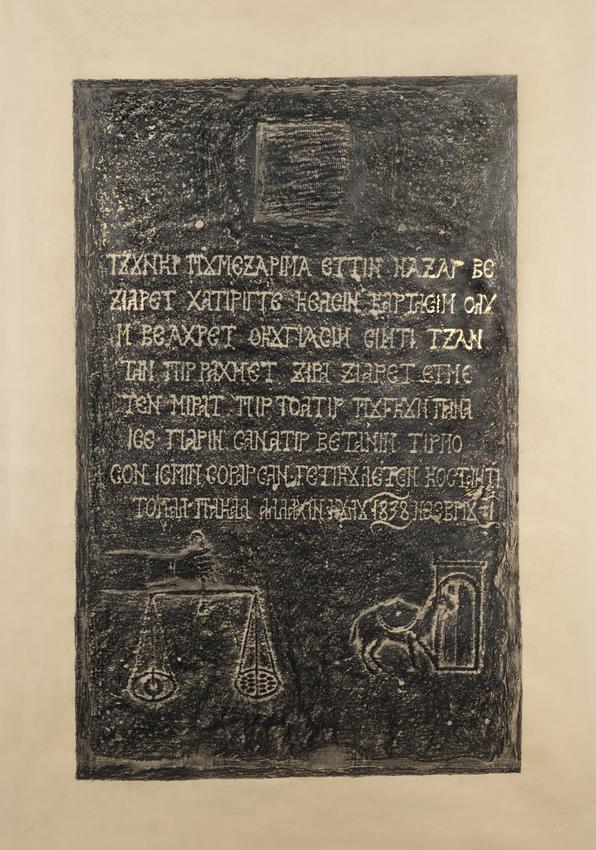

9 November 1(?), 1838. Gravestone [in Karamanli] of Koutsokonstantis, who was a grocer in Yedikule in Psomatheia and coming from Delmesos in Konya in Cappadocia, Marks: Scale [indicates profession] and a camel in front of a door [probably refers to trade with Cappadocia, place of his origin].

10. November 10, 1865. Inscription [in Karamanli] concerning two (?) persons. Here lies the barber Anastasios Konstantinides from Nigde of Konya. In Constantinople he used to pray at the parish of the Salmatomvroukion Monastery. In the upper place of the plaque engraved are two open pliers – barbers used to do teeth extractions.