While I have spent part of almost every summer since I was a child on the beaches of Vari and Vouliagmeni, and lived in the area for the past five years, it was only recently that I arranged to move my voting rights to the municipality. So I was somewhat surprised when the police arrived on my doorstep a month ago with a piece of paper informing me that I had been selected to take part in the electoral committee supervising the vote for all residents who had names starting between the letters Di and Zi (Z is much closer to D in the Greek alphabet than in the English one).

While waking up at 5.30am is not usually on my itinerary for most Sundays, I figured that in the interest of democracy and doing my duty as a citizen, I would sacrifice a few hours of sleep. I also thought that it might be an interesting experience to be on the frontlines of democracy for a day. The piece of paper also informed me that if I didn’t, I would face between three months and two years in prison, which helped firm up my decision.

So there I was at 7.00am as the ballots opened, drinking my third coffee and assembling the packets of ballots to be handed out to voters. People started arriving in dribs and drabs – first those with work to go to, then a wave of (predominantly elderly) church goers after mass, then a steady stream of people until lunch time at which point it dropped off, to pick again in the last couple of hours before the polls closed at 7.00pm (a word to the wise – if you are voting in Greek elections either early in the morning or between 3pm and 5pm are the times with the shortest queues).

FOSPHOTOS / Panayiotis Tzamaros

Each voter was given a packet of ballots and an envelope. They would duck into the secrecy of the curtained stalls, choose their preferred party, putting a cross next to their preferred candidates. They would seal the ballot in the envelope which they would subsequently (and invariably with a certain degree of ceremony) cast into the locked ballot boxes. The ritual was first followed for the municipal elections and repeated for the regional elections. After the polls were closed, we the electoral committee began the lengthy process of opening the boxes and carefully tallying all the ballots and crosses (electronic voting remains a gleam in some future interior minister’s eye for the moment). Yet the long-hand bureaucracy, while painstaking, is at least meticulous with a number of double and triple checks.

If there is one thing that the experience really brought home to me was that democracy is primarily about people. That may sound blindingly obvious but I believe that it is a truth that often gets lost in the swirling storm of figures and statistics that emerges from any election, particularly one at a juncture as critical as the one that Greece currently finds itself at. The sense of the individual is immediately swallowed up by exit polls and percentages with everyone from pundits to party representatives scrambling to parse the results before they have been properly counted. It is easy to feel as if one’s vote is nothing more that a speck of moisture in a thunderstorm.

Yet when you actually hold someone’s vote in your hands with the job of counting it, things become a lot more personal – despite the anonymity. It is a task that is simultaneously tedious and exciting. Aside from the actual vote, each ballot contains traces of the person who cast it. Some people fold their ballots with ruthless disciple, marking it with neat and precise crosses. Others are messier, hastily shoving it into a half-sealed envelope. One person even went so far as to include a handwritten note with his or her ballot complaining about the bus timetable and lack of accessible payphones (regrettably spoiling his ballot). Some of the crosses were emphatic, traced over several times while others were wavering – perhaps the evidence of indecision or maybe the workings of an older hand battling against Parkinson’s. They are votes made by people, and each one represents a deliberate decision made by someone who took the task seriously enough to show up on a Sunday and wait patiently in a queue with their ID card in hand in order to have their say.

And despite the political rancour in evidence on the airwaves between political rivals, the process among the voters – at least from where I sat, was remarkably peaceable. Aside from a couple of moments (one arising from a woman who refused to desist from loudly proclaiming her political views, and another from a couple of teenagers spoiling for a verbal confrontation with the police that they could brag about to their friends later) the process was calm and orderly. The overwhelming majority conducted themselves with a palpable sense of respect for the sanctity of the ballot box and the right of everyone to express their view in it. The small moments of kindness in evidence as people assisted the elderly and infirm to cast their votes, and the smiles triggered as wide-eyed children excitedly (and invariably with a degree of ceremony) dropped their parents’ ballots in the boxes for them far outweighed any evidence of division and acrimony.

FOSPHOTOS / Panayiotis Tzamaros

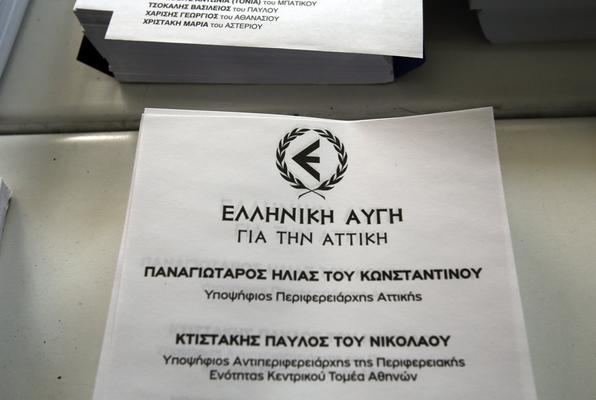

And so I was somewhat surprised when I opened envelope after envelope for the regional elections and saw that 45 out of the 303 people to whom I had personally handed a packet of ballots had voted for a party that I consider to be fascistic and dangerous. In my polling station regional governor candidate Ilias Panagiotaros of Hellenic Dawn (the rebranding of Golden Dawn for the local elections) came one vote shy of second place – in effect tied with SYRIZA backed Rena Dourou (The center left Giannis Sgouros was the runaway winner with 77 votes).

Yet during the day I had not seen 45 pumped up skinheads. I had seen people from my neighborhood. Which one of them had voted for Hellenic Dawn? The doctor? The bakery owner? That sweet little old lady?

One is tempted to think that 45 people out of the 303 are fascists, bad people who support a bad party who must be combated. To cry, kill the fascists! But I realized that what inspired me from the polling station 4543 was the unity I saw as people, individuals, came together in mutual respect to voice disparate opinions. That is what democracy is and what must be cherished. It was, in other words exactly the opposite of what I despise in Golden Dawn, a party which is built and thrives on division and an ‘us versus them’ worldview taken to such an extreme as to promote and justify racism, hatred and violence. There is a wealth of evidence indicating that Golden Dawn’s leaders are criminals who have established paramilitary groups and sent them on murderous missions. But labelling all Golden Dawn voters as evil fascists only plays into the hands of those leaders who claim political persecution when they are called to account for criminal behaviour.

FOSPHOTOS / Panayiotis Tzamaros

And this is where the other political forces need amend their ways. New Democracy has too often stoked the flames with its own harsh and divisive rhetoric, particularly when it comes to immigrants and ‘communists’, while SYRIZA – as it dreams of a people’s revolution – tends to denounce all the people that are not already following it, portraying itself as the one true hero here to save us from ourselves. If it really wants a landslide victory that its supporters hope for, it would do well to treat the 70% of Greeks who disagree with the party’s politics as something other than the enemy. One does not gather support with a pointed finger.

Why did 45 out 303 people vote fascist? I don’t know. There may well be 45 different reasons. But I do know that whatever their politics, they are people too who have committed no crime. Until they do or intend to, they should be treated with the respect that any citizen in a true democracy deserves.

Because beneath all of the electioneering and campaign slogans, democracy is fundamentally about people. And it is only ever threatened when we lose sight of that fact and our own, shared humanity.

Follow me on Twitter: @Suavlos