Editor's note: The present post kickstarts TPPi's series of Yanis Varoufakis guest op-eds, originally published on his blog, yanisvaroufakis.eu

The gist of today’s update is depressingly simple: Still, no sign of Greek-covery whatsoever. Indeed, every single indicator (including the ones that are presented as evidence of light at the tunnel’s end) points in a sadly negative direction…

For ease of distribution, this post can be downloaded as a pdf here. (Hungarian readers can read it in their language here.) Or just read on…

Below I round up the official data (extracted from the Bank of Greece and Greece’s National Statistical Office reports), up to December 2013, with some glimpses into January 2014. I begin with the real economy (GDP, investment, employment etc.), then discuss the money market (money supply, loans to the private sector etc.), re-state the obvious about Greece’s public debt, allude to the sorry state of the privatization drive and, lastly, conclude with some less conventional statistics; statistics that one does not encounter in any ‘normal’ country.

The Real Economy: The contraction accelerated in 2013

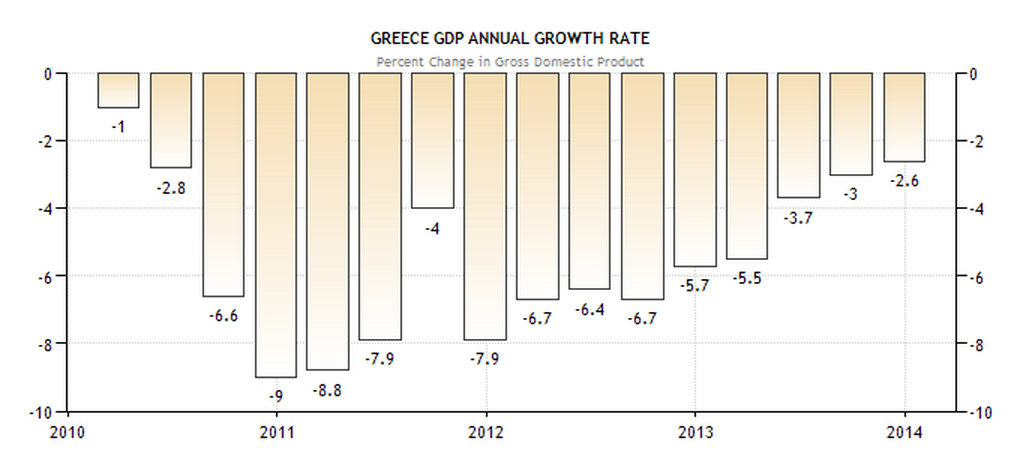

According to the government and the troika, 2013 was the year the recession decelerated. It did no such thing. While it is true that, in real terms, the rate of shrinkage declined (see following diagram), the reality is less heroic.

If we look at nominal GDP, a far more poignant statistic than real GDP in times of recession,[i] we shall be horrified to discover that the recession picked up speed in 2013, compared to the abysmal years 2012, 2011 and 2010. Indeed, as you can see from the figures below, whereas nominal GDP fell from 2011 to 2012 by a modest 1.1%, between 2012 and 2013 it shrank by a walloping 14%! In this sense, the Greek economy’s performance in 2013 was even worse than that of 2010 and 2011 – the first two years after Greece’s implosion.

Year Nominal Annual GDP ‘Growth

- 2010 -7.5%

- 2011 -8.9%

- 2012 -1.1%

- 2013 -14%

- 2009-13 -27.08%

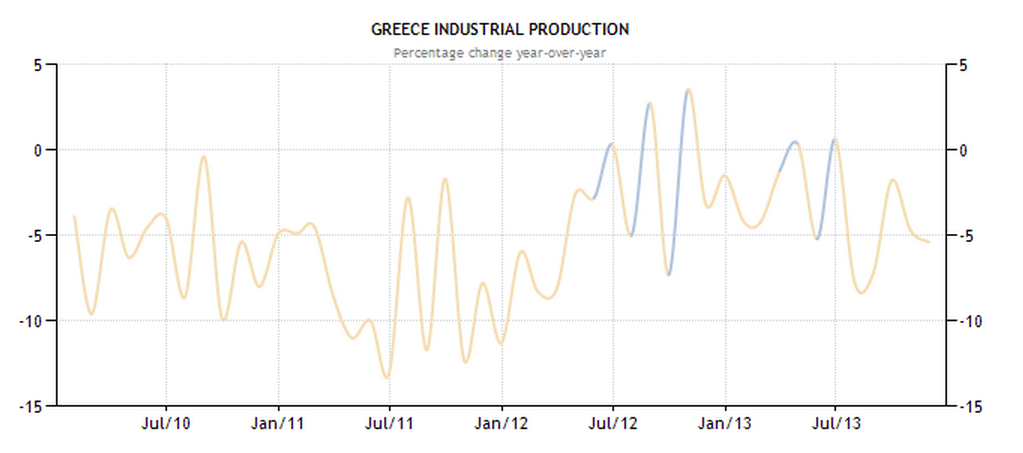

None of this is surprising if we look more closely at what was going on in the guts of the real economy. Manufacturing output was shrinking at between minus 4% and minus 15% for the first two and a half years of the Memorandum (2010-12). Once the ECB announced its OMT (summer of 2012), steadying the markets’ nerves, and Mrs Merkel confirmed that Greece was not to be booted out of the Eurozone (September 2012), there were some quarters when Greek manufacturing stopped shrinking further (see below the blips between August 2012 and July 2013). However, since last Fall, manufacturing output has started shrinking again. Indeed, the latest figures for January 2014 confirm this ‘incredible shrinking’ act: we are in minus 5% territory again.

What of industrial production more generally? No good news there either, I am very much afraid. As the following figure shows, Greece’s industry is continuing to shrink also by around 5% annually.

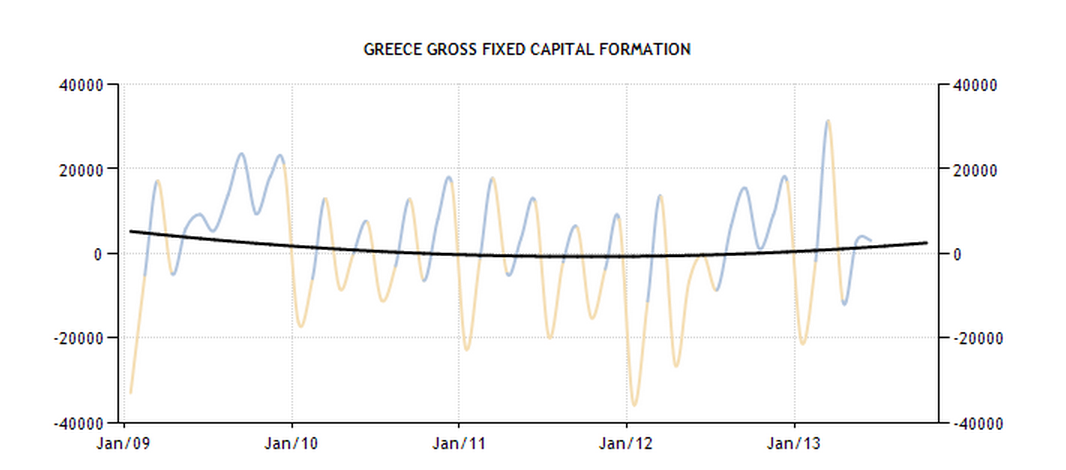

Might the government’s, and the troika’s, optimistic verdict that Greece’s economy is stabilising be due to good news on the investment front? A brief look at the diagram below confirms that nothing of the sort is in train. Gross fixed capital formation has flat-lined at 0%, leaving net investment firmly in negative territory.

What about employment? Any good news there? Did the huge reduction in minimum wages perform its magic, causing employers to take on a few more workers instead of investing in machinery? Is labour-capital substitution favouring labour over capital goods given the latter’s ‘cheapening’? As the following figure demonstrates, employment is continuing its downward slide, confirming that wage cuts in the midst of a multi-dimensional, cruel recession is bound to fail to instill the ‘confidence fairy’ in employers’ hearts and minds. The lower the minimum wages the more pessimistic Greek employers became that they can find paying customers for the wares that freshly hired employees might produce.

Lastly, you may have heard it being said that Greek car dealers registered a substantial increase in new car registrations in January 2014: up by more than 10% since the previous January. This is true. And simultaneously irrelevant. All that happened was that January 2012 had seen a 35% reduction in registrations (in relation to January 2011). Celebrating the fact that January 2013 was not as catastrophic for car dealers as January 2012 smacks of genuine desperation…

The Money Market

Another source of optimism for the Greek government and its EU-IMF supervisors was the banking system’s recapitalisation. Having borrowed €41 billion from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to hand over as capital to the bankers (without daring to demand that the Boards of these bankrupt banks are cleared of the bankers that saw the banks fail), the powers-that-be proclaimed that liquidity was about to hit the markets. Indeed, the Greek PM, Mr Samaras, made it his crying call in early 2013: “Once the recapitalisation is complete, by the Spring of 2013”, he kept repeating like a stuck vinyl record “businesses will regain access to loans and Greek-covery will be ours.” This, of course, was never going to happen – for the simple reason that the bankers were hiding the true capital needs of their banks, clinging on (with the government’s and Central Bank’s shameful aiding hand) to their majority stakes. Only a few days ago, the IMF and the ECB began frantically to signal that Greece’s banks need at least another €20 billion. (Click here for a recent report in the Financial Times.) And since the proof of the pie must be in the eating, the following diagram makes for interesting reading: Not only has liquidity to the private sector not returned but, in addition, the rate of its decline has risen sharply throughout 2013. Indeed, according to the Bank of Greece, credit fell 3.9% in December 2013 and, even more ominously, fell again by another 4% in January 2014.

We are now in the ludicrous situation that the Central Bank of Greece is hailing the banks’ recapitalisation as a success story, criticising the IMF for exaggerating the banks’ capital black holes and invoking Blackrock’s recent report which only found the Greek banks’ asset books to be short of the latest data from the Bank of Greece show a further contraction in bank lending during January, reflecting net deductions from households and corporations. Does the Governor not know that Blackrock did not take non-performing loans into account when making these calculations? Has he not read his own Annual 2013 Report which reports (in admittedly hidden sections) that the rate of non-performing loans has increased from 29.3% in the second quarter of 2013 to 31.2% in the third? Of course, the less is said about the current Governor of the Bank of Greece, and his cosy relationship with the bankrupt bankers (whom he served as an employee until he was appointed Governor), the better. (But do see here and here two excellent articles in the New York Times about his murky role.)

Turning now to the money supply, the following diagram confirms the lack of élan in the Greek marketplace. The supply of M2 money was falling steadfastly from the moment the Greek state was found to be insolvent, and the economy embarked on its never-ending recession, until the summer of 2012. Around election time, when the establishment parties were investing in fear of Grexit in order to maintain their hands on the levers of power, money disappeared in boxes, under mattresses etc. Some of that liquidity returned by early 2013, alongside with a fraction of the bank deposits that had fled the country. For the rest of the year, however, M2 has been flat when even a modicum of growing economic activity would have caused M2 to rise. It did not. Why? Because economic activity has not picked up (as I argued above).

![Greece - Money Supply M2]()

Privatisations

2013 was a disastrous year for the privatisation program. The spectacular failure to sell a public monopoly to Gazprom (which refused to buy at almost any price, citing the deflationary forces raging in the Greek economy as the reason for its withdrawal), left the government with a single success story: the sale of the state lottery OPAP to a shadowy consortium at a low, low price and under conditions that will prove, undoubtedly, to be detrimental to the government’s long term benefits.

Perhaps the most distressing news from the privatisation front is that it seems impossible to stage an auction; not even for supposedly valuable assets. Once Gazprom walked away from the energy market, the privatisation of the public energy company just fell through – for here was no other bidder. OPAP too was, in the end, sold to the only bidder. The fact that a goose laying golden eggs (i.e. a monopolistic lottery) was not only sold at a knock-down price but was also incapable of drumming up competitive bidding is quite telling. The latest of this trend is perhaps the greatest real estate deal Greece has to offer: The old Athens airport site at Hellinikon. Even though Hellinikon is a prime sea-side plot more than twice the area of London’s Hyde Park, and located next to the most upmarket suburbs of Athens, once more only one bidder[ii] appeared during the privatisation process.

Public Debt and Bond Yields

The Greek government is celebrating that Greek government bond yields have fallen to less than 5%, from 30% eighteen months ago. Is this not cause for some celebration? It is, but only for those ignorant of the state of Greece’s public debt structure!

Following two massive official loans (one in 2010, another in 2012), Greece’s debt remains more or less what it was when the country imploded in early 2010 – north of €310 billion (while GDP is 27% lower, of course). So, what did these official loans achieve? They simply shifted Greece’s public debt from the private sector to the official sector. In combination with the PSI (haircut of bonds held by the private sector) of the Spring of 2012, this substitution meant that only 10% of Greek government debt remains in the hands of privateers – primarily hedge funds. Also, and this is important to the hedge funds’ calculations, the bonds remaining in private hands are all English Law contracts, which make it hard for Greece and Europe to haircut them again.

The gist of this is simple: It is now common knowledge that, while Greece’s public debt is spectacularly unsustainable and will be haircut again (one way or another), the bonds still in private hands will not be touched. It is simply not worth fighting the vulture funds over them in the courts of London or New York as they represent a small portion of the total debt. This common knowledge inspires confidence in the bond markets about these few, remaining post-PSI Greek government bonds. Thus the paradox: Everyone knows that Greece’s debt will be restructured and yet no one really fears that the bonds still with the private sector will be haircut. Is it any wonder that their yields have fallen? No, of course not. Is that fall a sign that Greece’s creditworthiness has risen? None whatsoever. (For that, we would need to observe the yields of fresh issues of Greek government bonds. Only there haven’t been any fresh issues since… 2010.)

Looking forward, Berlin’s Plan A for Greece’s public debt is that:

(1) The Greek debt will only very mildly restructured in the summer of 2014 (with no haircut to the principal, a long extension to the repayment schedule and a small reduction in interest rates; i.e. with a haircut of its present value, but not its face value)

(2) The ad-infinitum-bankrupt Greek state will be allowed to return to the markets, by the third quarter of 2014, under the oversight of the ECB whose OMT threat will ensure that investors are prepared to lend, at interest rates around 4% to 5%, to a state that they know is bankrupt (and which they are prepared to lend to only because of the ECB’s OMT); and

(3) The above will be conditional on another troika-administered Memorandum of Understanding.

In summary, new bonds will be issued when steps (1), (2) and (3) have been taken, and Athens proves that it can acquiesce fully and reliably to such a plan, even after the present government has folded its tent. The essence of Berlin’s plans for a third Greek ‘bailout’ is that it will not be funded by Europe’s taxpayers through the ESM but which will, instead, be funded by privateers under the pressure/guarantee of the ECB’s OMT – assuming, of course, that the latter remains a credible threat following the googly that the German Constitutional Court threw toward the OMT’s wicket recently. But that’s another story…

Current Account

Have you heard the news? Greece is now a surplus nation! At least in current account terms. Is this not good news? If it were due to a significant rise in exports, and some strong import substitution (with domestically produced goods and services edging imported competitors out), it would have been good news. Only this was not the reason Greece has a current account surplus today. The sorry reason for this surplus is that the deepening recession shrunk imports by a further 11% while tourist income last summer rose a little as Turkey’s and Egypt’s political troubles diverted tourists to Greece’s shores. What about exports? I am afraid that they were lower in 2013 than they were in 2011, when they were much lower than in… 2008.

Still, the news media were only too quick to hail the miracle of a Greek current account surplus. Foolish as they tend to be, they added that “Greece has not posted a current account surplus for many decades.” That’s quite so. What they, however, failed to add is the year when Greece’s current account was positive last. Let me reveal it for you: It was 1943 – under the Nazi occupation, when Greeks could not afford to eat (let alone import goods from abroad) but still managed to export a few oranges, a few apples etc. Today, once more, the collapse of domestic demand, even in the absence of an export drive (due to the lack of credit to export-oriented businesses), has produced a 1943-like situation. Not a cause for celebration; at least not in my book.

Epilogue: Still a failed state

Europeans must grasp a simple fact: Greece has been, and remains, a failed social economy. Rumours of its recovery are just that: ill-motivated rumours![iii]

Besides the wretched diagrams and data above, there are other facts on the Greek soil that corroborate the characterization of Greece as a failed nation-state. Here are some:

- There are 10 million Greeks living in Greece (and falling fast due to migration), ‘organised’ in around 2,8 million households that have a ‘relationship’ with the Tax Office. Of those 2,8 million households, 2,3 million have a debt to the Tax Office that they cannot service.

- 1 million households cannot pay their electricity bill in full, forcing the electricity company to ‘extend and pretend’, thus ensuring that 1 million homes live in fear of darkness at night while the electricity company is insolvent.

- Of the 3 million people constituting Greece’s labour force, 1,3 million are jobless.

- Of the 1,3 million jobless only 10% receive unemployment benefits. The rest must fend for themselves.

- Of those who work in the private sector 500 thousand have not been paid for more than three months.

- Contractors who work for the public sector are paid up to 24 months after they provided the service and pre-paid sales tax to the Tax Office.

- Half of the businesses still in operation throughout the country are seriously in arrears vis-à-vis their (compulsory) contributions to their employees’ pension and social security fund.

Nothing further needs to be added here to convey the true picture of today’s Greece. Except, perhaps, to suggest that, when one hears buoyant accounts of Greece’s recovery, one has a moral duty to respond with an ironic smile.